BREAKING

BARRIERS

Quarterly Report

June 2022

Reimagining Resilience as a MAP for Recovery

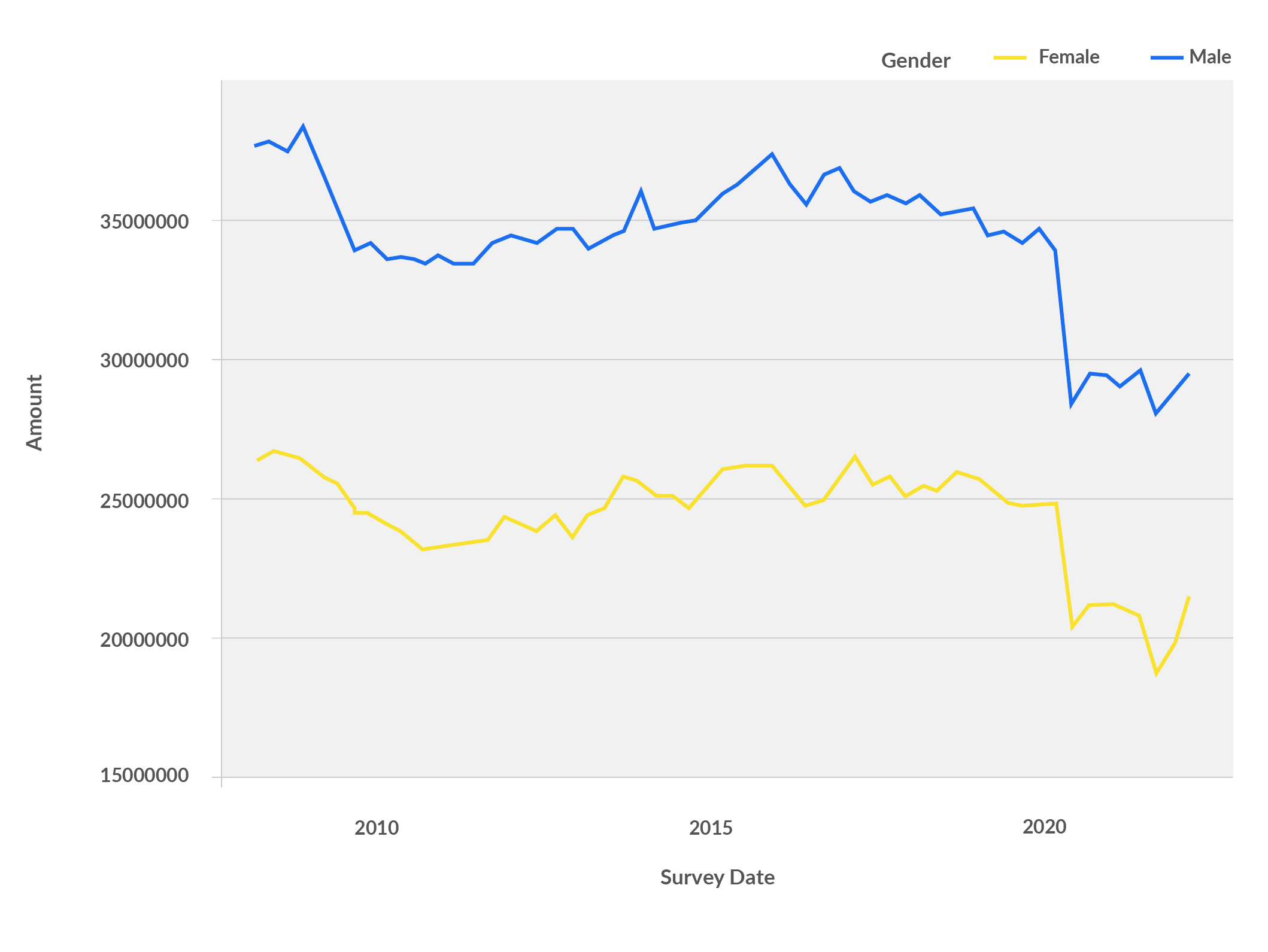

The latest Quarterly Labour Force Survey results suggest that the number of employed young people has increased for a second quarter in a row. While this is the highest this has been in the past two years, this slight bounce-back is cause for very cautious optimism, as employment remains considerably lower than pre-lockdown (Statistics South Africa, Quarterly Labour Force Survey, Q2:2022).

The employment journeys of young people have been characterised by resilience–a word that has come under recent scrutiny. While it is true, resilience alone in the face of crisis is not what will get us through. Resilience needs to be coupled with intentional investment and support to address our country’s multiple overlapping crises which demand ‘resilience’ in the first place.

So how do we move beyond using resilience to speak about merely enduring these crises, and towards using resilience to get ourselves out of the crises? By finding where resilience occurs and supporting those initiatives, ideas and communities.

Our analysis reveals that very few sectors, if any, have been able to return to pre-pandemic levels of employment, and certainly not to levels before the 2008 economic crisis.

Furthermore, the economic recovery continues to favour contract jobs over permanent employment as companies hedge against further uncertainty. Now, more than ever, we need to focus on resilience–not just celebrating the endurance of crises alone. But rather, focusing on those aspects of the labour market that will enable us to collectively bounce back to the road to recovery.

This Youth Month, Harambee outlines three aspects of resilience – resilient incomes, resilient sectors, and enablers of resilience – that could serve as clues to help us bounce back out of these multiple, overlapping crises.

KEY INSIGHTS FOR

THIS QUARTER

INSIGHT 1

Resilient income: young people hustle their way out of poverty, we need to help them make it less precarious

The economic downturn and resulting job losses in the formal sector has meant that more and more young people were forced to start hustling to earn money. While this is often precarious and volatile, hustling provided precious resources to young people in the face of a contracting economy.

There are around 1.2 million young micro-entrepreneurs in the informal sector. Our analysis suggests that most micro-entrepreneurs are black African (88%) and that youth make up 40% of the informal sector. The majority work in urban areas, with the retail and wholesale trade sector representing the most popular sector. The decision to enter the informal sector is both necessity and opportunity driven. 40% of participants describe that they couldn’t find a job or saw it as their only option, while 36% had entrepreneurial aspirations or saw an opportunity in the market.

The young people we surveyed described a range of entry barriers preventing them from entering micro-enterprise–including structural factors such as lack of suitable premises, equipment or perception of insufficient customers. Young people also feel insufficiently encouraged by friends, family or community members–who make them believe it is a bad idea; they describe that people in the informal sector are often judged, looked down upon or not taken seriously.

Harambee’s own database suggests that most young hustlers have irregular and volatile income, with monthly figures ranging from as low as R 200 to R 4,000–but often unpredictable and highly volatile. Our data also suggest that providing services (such as braiding hair or digital support ) vs. selling goods (such as selling snacks and clothes) is on average more profitable for young people–and that women are more likely to engage in selling of goods, impacting their profits (Harambee Breaking Barriers, 2020).

Despite its volatility, there is also a sense that hustling offers a bit of flexibility. Recent research suggests that “hustling, while uncertain and precarious, had the advantage of giving you more control over what you did with your limited resources.”

Thus, while hustling represents an incredibly important source of resilient income for young people, we need to understand how to make this source of income more consistent, less volatile, and to reduce barriers to entry with intentional investment and support.

Figure 1: Young person with resilient income

INSIGHT 2

Resilient sectors: coordinated investment in the face of growing demand

In the first quarter of 2022 there were ± 5.1 million young people aged (18-34) in employment – an increase of nearly a quarter of a million young people employed in the last quarter of 2021, and the first time since the start of the pandemic that there has been two consecutive periods in which youth employment has increased. However youth employment is nowhere near pre-pandemic levels and recovery remains slow.

Community, social and personal services accounts for the majority of employment gains for youth. While hard to confirm for sure, this is possibly shaped by the Presidential Employment Stimulus such as the Department of Basic Education’s teaching assistant programmes, suggesting that this should continue to be an area of focused investment to ensure opportunities and wage gains are sustained. But there is also some hope in other sectors.

Take for example the financial intermediation, insurance, real estate, and business services sector. This sector employed 2.54m young people before the pandemic–and now, even despite some losses, is the closest to returning to pre-pandemic employment levels. Suggesting that the sector holds promise to help deliver us out of this crisis.The sector continues to be an umbrella for many kinds of jobs, it demonstrates potential for growth in the face of the crisis.

During and despite the pandemic, the South African Global Business Services (GBS) sector created more than 50,000 cumulative new jobs (GBS Sector Job Creation Report: Q3 FY 2021), with key investments from international companies like Amazon, Webhelp and TransUnion. Globally, the impact sourcing market is around 350,000 FTEs and is predicted to increase. With all evidence pointing to the impact sourcing and global offshoring sector as the next “manufacturing sector” with the potential to absorb large numbers of young people into the workforce of the future.

According to a report by McKinsey, cumulative jobs in the South African GBS sector could reach as high as 775,000 by 2030. A Master Plan, developed with the Department of Trade, Industry and Competition (DTIC), alongside strategic public, private and social partners, has been signed with the intention of sustaining the growth and trajectory of the sector and creating between 250 000 and 500 000 cumulative new jobs in the sector by 2030.

This sector is evidence of real resilience, even in the face of the pandemic– “(South Africa’s) GBS export market had seen a 24% increase in Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) between 2014 and 2018 and then a jump to 34% in 2019, tapering to 15% CAGR in 2020 with the COVID-driven lockdowns,” according to Andy Searle, former CEO of BPESA. These growth numbers represent twice the growth rate of the sector globally, and three times faster than key competitors, which provides clear evidence of the priority status of the sector and confidence from the investment community.

If we look to these sectors as examples of resilience, we could indeed find the clues that will help us bounce back to economic recovery.

Figure 2: Industries built on firm foundations

INSIGHT 3

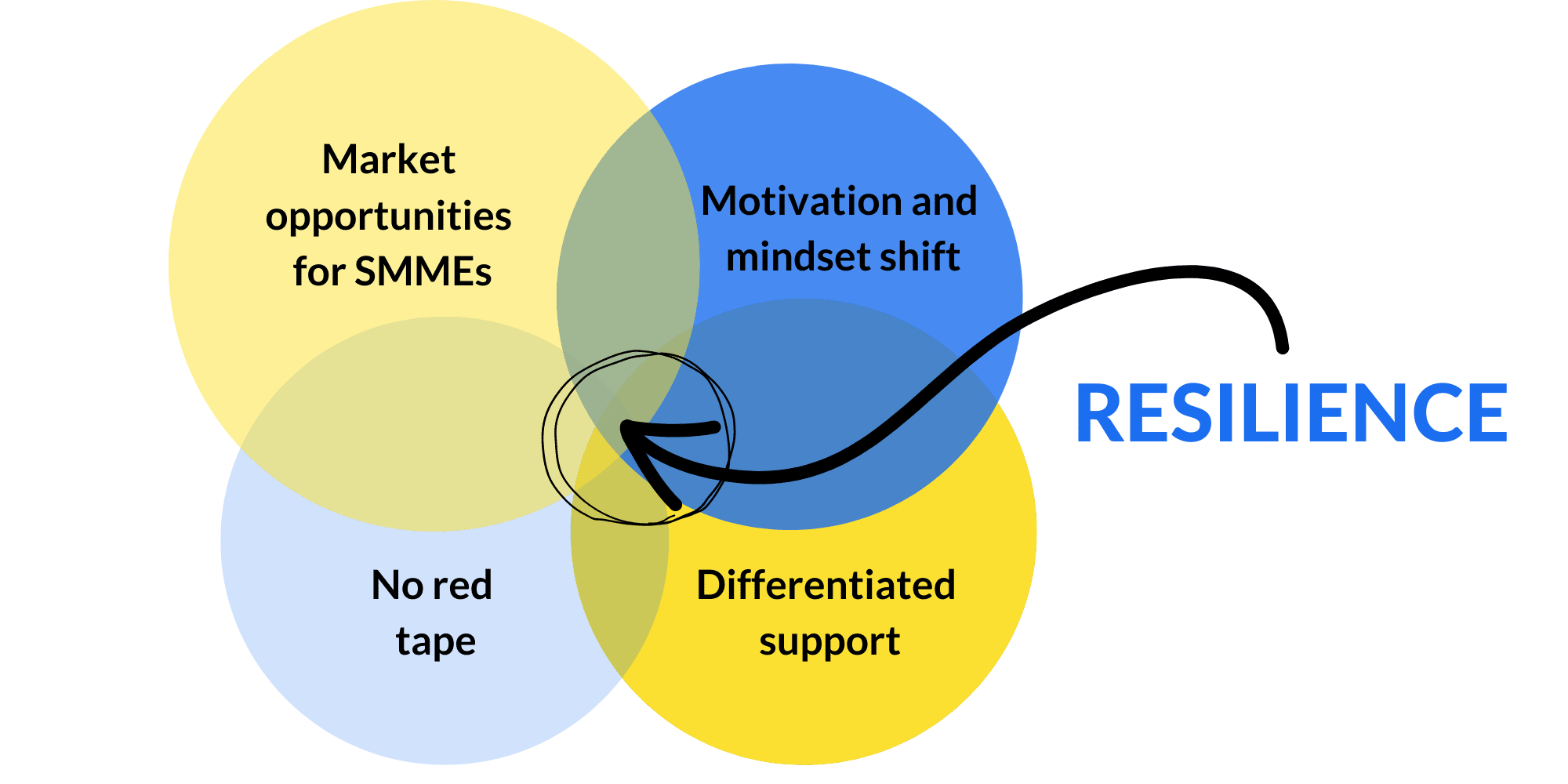

Enablers of resilience: SMMEs will be an engine of growth, but SMMEs need both targeted and differentiated approaches

Small, micro, and medium enterprises contribute a third of South Africa’s GDP, but are hardest hit and most vulnerable to shocks like the pandemic and financial crises. Prior to the pandemic, employment in the SMME sector grew by 1800 jobs per day (CDE 2021). If SMMEs are the growth engine that will accelerate economic recovery, we need to address the blockers and enablers that can help restore these wheels into motion.

Contrary to popular belief, it is not for lack of entrepreneurial intent or orientation that SA’s informal economy does not absorb more young people. From the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (GEM) survey for 2020, South Africa ranks sixth out of 12 in terms of total early-stage entrepreneurial activity as a percentage of the adult population. By contrast, the percentage of the population owning an established business is very low, at 3.5 percent, which puts us near the bottom: 44th out of 50 countries. Clearly this is not an issue of a lack of motivation alone.

SMMEs typically cite red tape as some of the biggest barriers to entry–including bureaucracy around the labour regime making it difficult to hire effectively, and the behaviour of local government, including bylaws, police regulation enforcement, harassment, and enforcing restrictions. Our existing incentives and tax regimes also skew towards supporting the growth of a formal economy–South Africa’s heavily regulated environment supports the expansion of formal businesses, who encroach into most niches in the economy that would have otherwise been taken up by informal firms.

South Africa’s leading authorities on the informal economy have suggested providing a “menu” of elements of formality for SMMEs at various stages of development, rather than considering formalisation as a forced, linear process. Ideas include amnesties for unregistered firms, access to free marketing for registered firms, and using receipts as lottery numbers, which would give customers an incentive to ask for a receipt. Expanding ease of access to labour such as reduced barriers to participation in Youth Employment Service, etc. could enable SMMEs to access much-needed human capital for growth. The Black Business Council has suggested one-stop-shop mobile trucks that will go to townships and villages to rollout tax, company, and employee registration services. Late payments from big corporates have a huge impact on cash flow of small businesses– even in November 2020, 50 large businesses needed to make a public commitment to pay SMEs within 30 days, and that, apart from Massmart, none of the big retailers was part of this initiative (Ed Glaeser, CDE)

And finally, our support for our young hustlers could be simpler and easier to access. From a study conducted by Harambee, only 2% of participants reported that they had received support from the government or municipality even though 15% applied. Similarly, only 2% got funding or support from companies even though 10% applied. Current support programmes were considered to be helpful but had a limited reach, especially due to a lack of information as 49% didn’t know about the programmes and 42% didn’t understand the process. Making existing support more visible and accessible can help our young people step onto the entrepreneurial ladder, and use their latent resilience and drive to power an economic recovery.

This Youth Month, let’s not not use the word resilience to simply celebrate endurance. But let’s rather investigate the spaces where resilience occurs – and increase our support of these initiatives, sectors and enablers – such that resilience indeed, can bounce us out of the unemployment crisis.

Figure 3: SMME enablers

Youth employment trends

NEED MORE INFORMATION?

WANT AN OFFLINE VERSION?

Stay Connected

Stay Connected