SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

The latest QLFS figures suggest that South Africa’s unemployment challenge remains intractable and exacerbated by COVID. Across the globe, spending on COVID-19 fiscal stimulus has been unprecedented in scale and scope. South Africa has spent R12.6b on the employment stimulus programme, significantly more than peer countries in terms of COVID relief. To date, over 550,000 people have benefited from this, with nearly 320,000 benefiting from the Department of Basic Education (DBE) programme alone. The scale of this investment has led to increased focus on if and how these types of help-to-work programmes perform at scale; in particular, whether efficiency at scale comes at the cost of inclusion and long-term dividends. South Africa’s COVID-19 stipend programmes have sought to leverage technology, intragovernmental alignment, and social partnership to overcome this trade-off, and the data suggests it is working—the theme of this edition of Breaking Barriers.

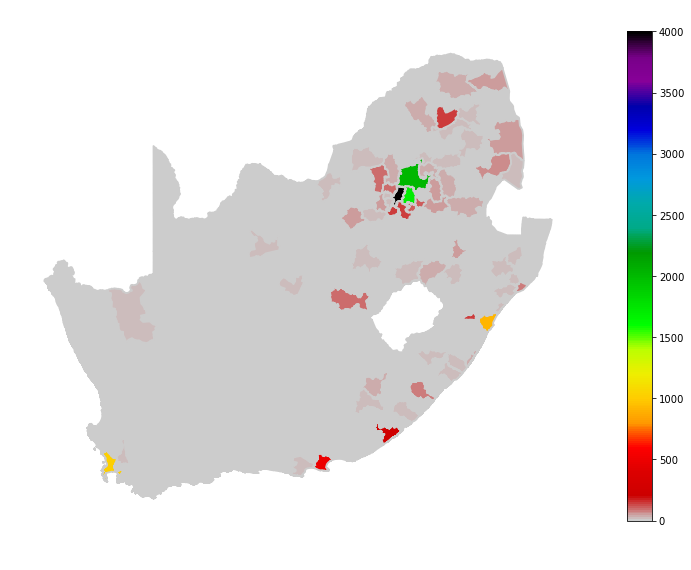

For years, our research has revealed that distance from an employment opportunity is a significant barrier to inclusion. South Africa’s employment stimulus has recognised this and made it a design point of several programmes. Among those that stand out: the Department of Basic Education (DBE) school assistant programme, now beginning its second cohort.

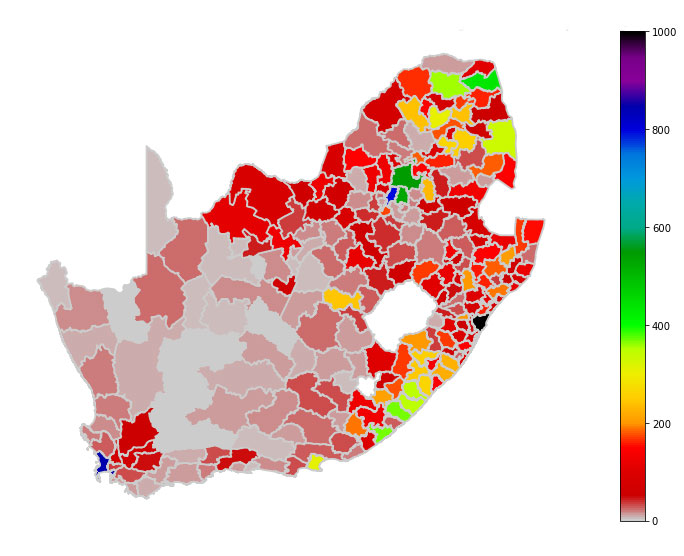

The DBE programme has achieved unprecedented reach: nearly 320,000 youth have been employed since its launch in November 2020. For the next cohort, over 940,000 young people applied via the zero-rated recruitment platform SAYouth.mobi in a matter of weeks. For a programme of this scale, spatial data shows a geographic scope that is also unprecedented: 23,000 schools across 75 school districts created positions, putting approximately 300,000 applicants within walking distance of the school they were placed in. To do this, the system checked latitude and longitude coordinates for each school, and that data was used not only to ensure South African and provincial eligibility, but to analyse distance from each work-seeker’s residence as a factor in ranking applications. The resulting map of public employment wage recipients shows the extraordinary power of the programme in bringing work to what were formerly ‘jobs deserts’1

Optimising for this spatial dimension seems to have driven inclusion on other important dimensions too: 73% of applicants were female, and 76% had a matric qualification, adding further weight to Harambee evidence that transportation is a major intersectional barrier for young women’s employment.

The majority of public employment wage recipients are new, first-time labour market entrants—formerly invisible or unreachable young people for whom the DBE programme created their first opportunity to work and earn within range of where they live.

At least 58% of recipients in programmes that created jobs were women, and 84% were youth. The stimulus programmes are reaching those whose barriers to economic engagement were previously insurmountable—and they are doing so at scale and speed.

Figure 1: Youth Employment Density by South African Municipality (2020)

Source: Harambee EJ* Survey (2020) n = 161,097

*EJ responses for 2020 who reported having a job were overlayed with municipality. Grey indicative of a jobs desert

Figure 2: DBE Teacher Assistant School Locations by South African Municipality (2021)

Source: Density of school location by municipality for DBE teacher assistant placements.

*DBE data showing the location of schools where teachers assistants were placed per municipality

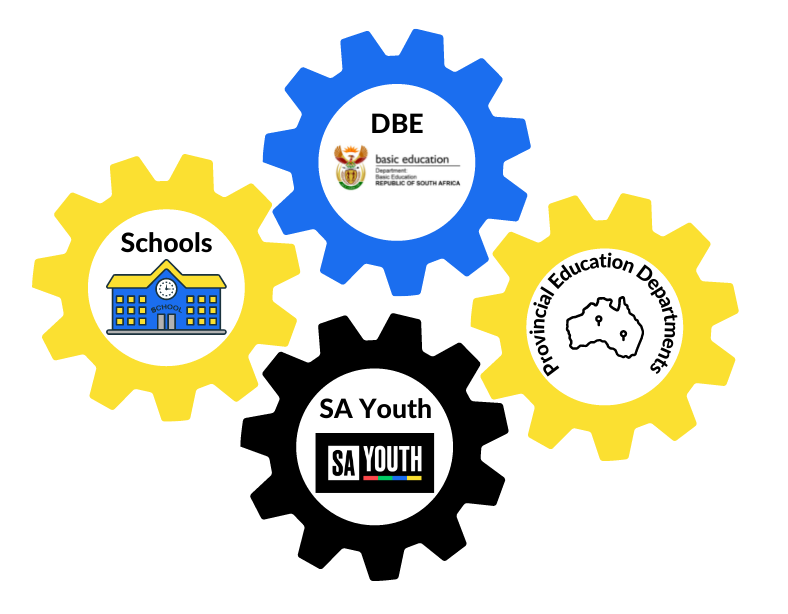

The DBE programme and others like it are the product of massive multi-stakeholder collaboration. Many entities within and beyond government partnered at all levels of the operation, from national, provincial and local governments, to private sector partners, to individual schools and their principals. This web of actors vastly proliferated the channels through which young people could encounter and access the new opportunities created by the programme. Young people could access the SA Youth platform from NYDA, libraries and DEL sites across the country, through facilities made available on the premises, resulting in extensive coverage as shown in the Youth Explorer Geo site when selecting the ‘NYDA’, ‘DEL facilities’, ‘Public schools’ and ‘Libraries’ filters. This was a key driver of the inclusion levels seen in the data noted above.

Partnering went beyond simply plugging different locales into a network. Many government departments combined resources in a single, integrated programme design that required ongoing cross-cutting collaboration, with clear shared processes and unique roles for each partner outlined from the outset. The DBE led umbrella implementation management, advocacy and awareness campaigns, while provincial education departments (PEDs) to mobilised stakeholders and advertising efforts regionally to drive work-seekers to mobi-sites and access points. Schools themselves played an active, coordinated role leading outreach in community hubs, shortlisting, interviewing and appointing candidates.

It would not have been possible to create from scratch an infrastructure capable of attracting and processing this number and range of work seekers, with the speed and efficiency required by crisis conditions. Deep partnering allowed the DBE programme to leverage existing assets controlled by disparate players and systems, and point them at a single goal. As well as delivering its own outcomes, it has created a precedent for how to cooperate at speed and scale on complex problems that no one entity can solve alone—and it has generated the new relationships, process and data required to do so, such as the new accurate, location-specific data set on young people and schools that simply did not exist before. This multi-stakeholder partnership is itself a new asset in the system that can now be deployed against a range of social and economic objectives.

Figure 3: Collaboration between national and provincal government, SA Youth and schools delivered a public employment programme that works

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021

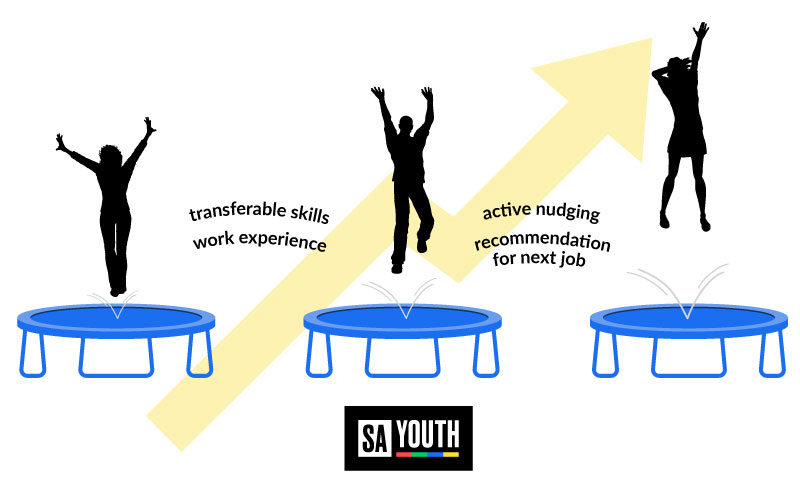

Public employment programmes are sometimes critiqued for their short duration: when the wage ends, the recipient is ‘bounced out’ and—without data to show otherwise—back to where they started. However, there is strong evidence that these wages can result in a fiscal multiplier. Studies on India’s employment guarantee scheme, the largest public works programme in the world, have demonstrated that effectively-administered public employment programs could increase low-income household earnings by 13%, with 90% of these gains driven by increases in market wages and private-sector employment.2

But few large-scale public works programmes have been backed by the infrastructure required to track, let alone drive, long-term employment outcomes at the individual level. South Africa’s successful COVID-19 stipend programmes mark a departure from that limitation with their use of new digital platforms like SAYouth.mobi.

SAYouth.mobi creates ongoing forms of value for participants in at least three ways. One, it is an aggregator of opportunity across all economic sectors. By completing the application process, wage recipients send a strong, qualified signal of employability that can be “read” by a much broader swathe of the labour market. Two, our research suggests that by initiating intelligent matching based on these signals, the platform can unlock savings of approximately R550 per person per month on work-seeking costs such as transport, data, printing and postage. Our data suggests that this cost savings could be sustained beyond the wage, since the network offers a free or low-cost way to apply for future opportunities, and filters these based on factors such as proximity (saving the successful applicant commuting costs). Three, SAYouth.mobi goes beyond matching. It plays an active role pathwaying public works programme participants from a “foot in the door” towards the next opportunity, by automatically enhancing their profile.

DBE programme data shows this is already happening: over 80% of the first cohort of school assistants reported learning new skills—like administration, communication, teaching, interpersonal skills—that are transferable to other jobs available through the network. Harambee’s own data suggests that work experience improves a work-seeker’s likelihood to earn a higher salary in the future and get a higher complexity job.

Over the past decade, we have seen a significant level of self-placement for such young people who have received even a small amount of support, training or employment via our network—the bounce-back, or ‘trampoline’ effect. With the same network infrastructure beneath public works progammes, we can now track and assign ROI to that effect more confidently. What’s more, by keeping people in a network over the long term, SAYouth.mobi creates mass longitudinal data sets that reveal patterns of success we can replicate across the labour market.

Figure 4: The DBE SA Youth partnership provides evidence that fiscal multipliers exist for stipend income

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021 / South African Government, 2021 https://www.stateofthenation.gov.za/employment-stimulus-dashboard

The most immediate requirement for any crisis stimulus is to provide income support. The COVID-19 stipend programmes have done this for hundreds of thousands of recipients, putting an estimated R9b into the pockets of South Africans in the form of wages and/or savings. The question is whether they unlock more value than they spend, and the evidence suggests that they do. From our data and others’, we now know that when public employment programmes work well, they drive both inclusion and efficiency, and may directly impact economic growth. South Africa’s employment stimulus programme, powered by SA Youth and driven by a national coalition, has created a new national asset with the potential to become an engine of economic transformation.

1 Youth employment density calculated from Harambee ‘Employment Journey’ data for 2020, reflecting the total number of youth who said they were employed in a job, per municipality. Teacher assistant school locations by municipality from DBE data.

2 Authors are economics faculty members at UC San Diego (Karthik Muralidharan and Paul Niehaus), and the University of Virginia (Sandip Sukhtankar), access the column at https://www.hindustantimes.com/columns/strengthen-nregs-to-support-the-rural-economy/story-uOlHMjpeqcpe6fVXWekeRI.html.

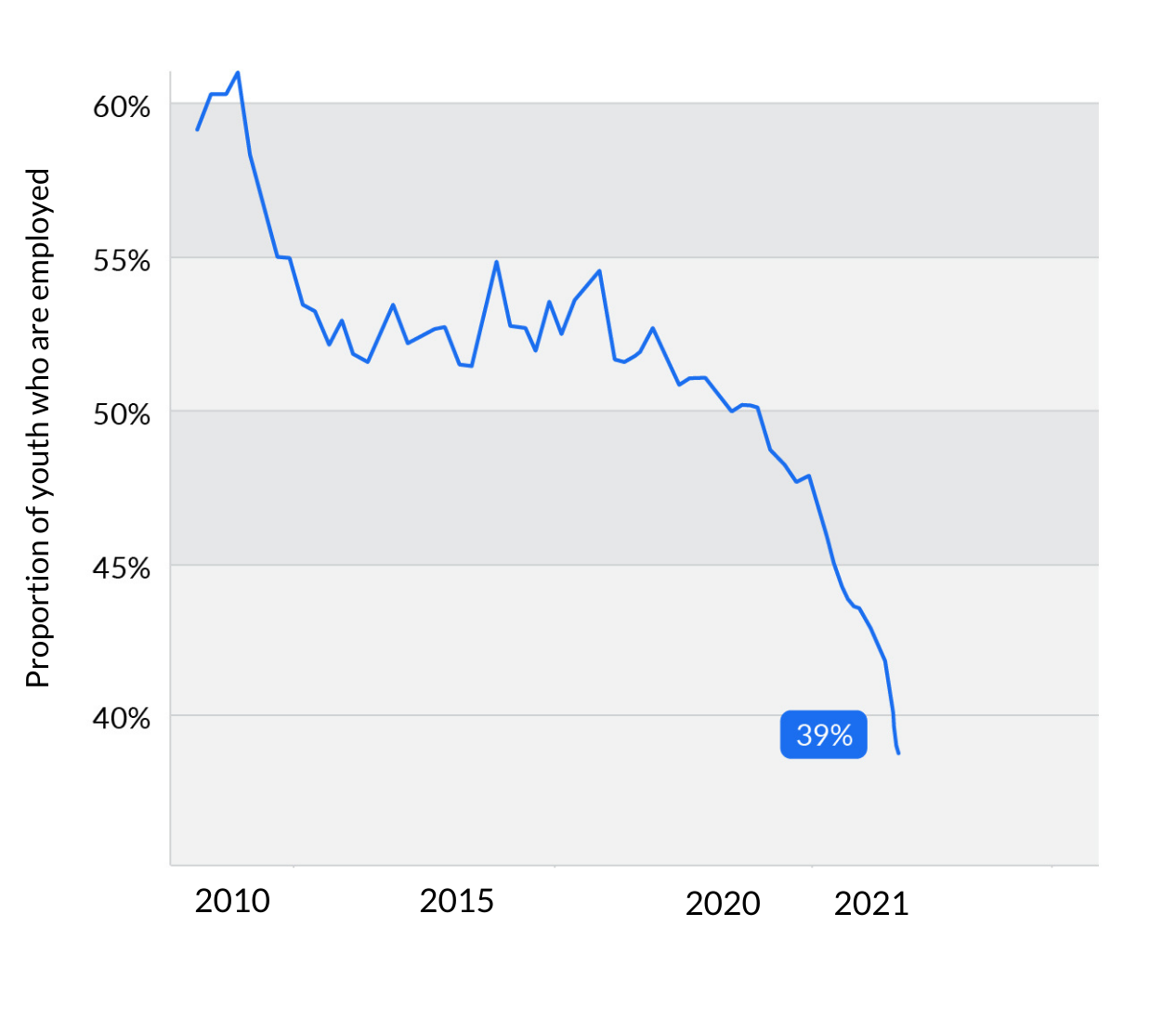

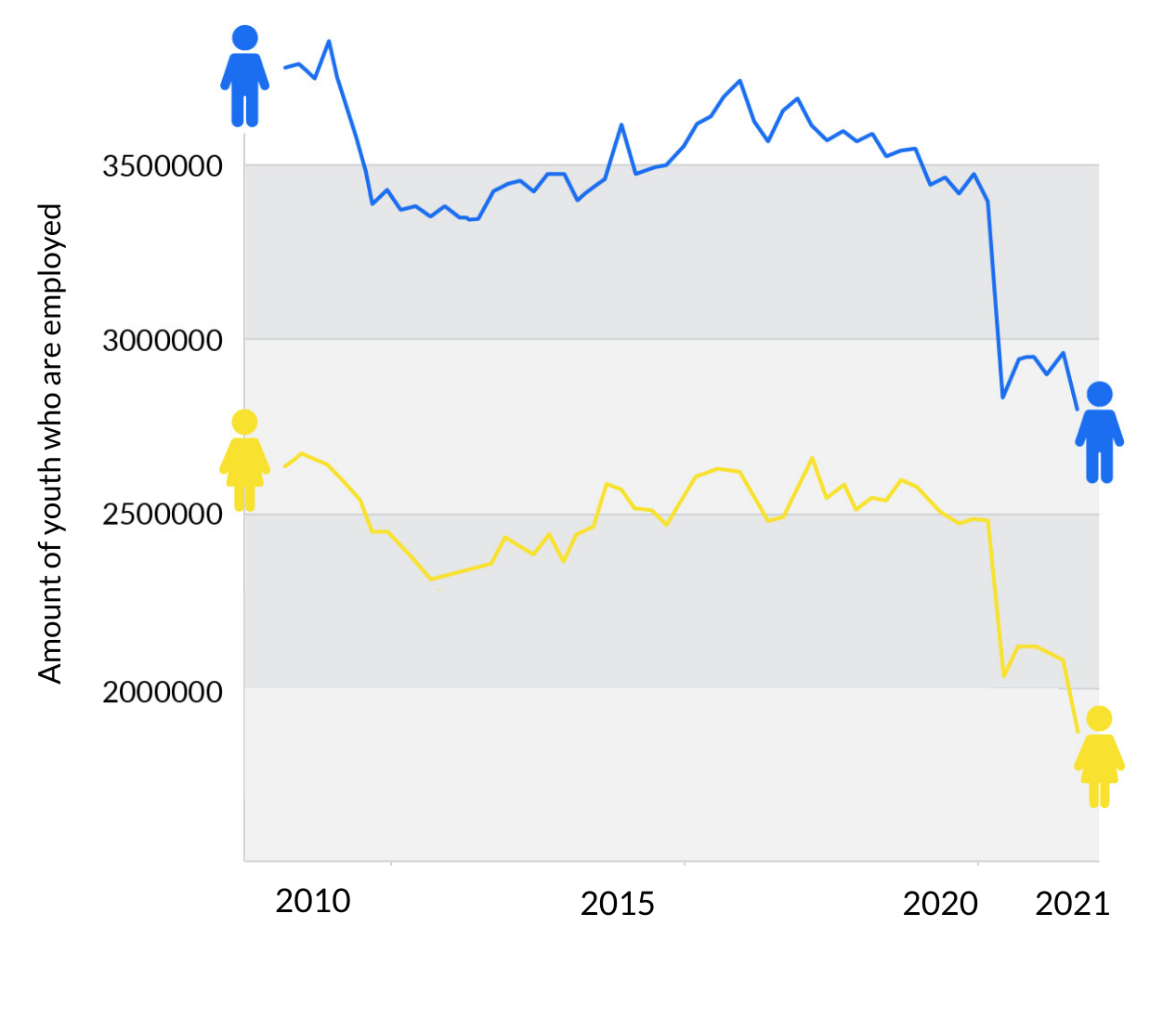

Stats SA QLFS headline: although unemployment is down, so is employment; by 660,000. Discouraged work-seekers also grew by 550,000. Youth aged 15-24 years and 25-34 years recorded the highest unemployment rates of 66,5% and 43,8% respectively. The overall NEET rate increased by 1,6 percentage points and approximately 3,4 million (33,5%) out of 10,2 million young people aged15-24 years are NEET.

Figure 5: The proportion of youth employed in this quarter dropped to 39%

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021 / Stats SA QLFS, November 2021

Figure 6: The amount of male and female South African youth who are employed

Source: Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator, 2021 / Stats SA QLFS, November 2021