SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

Inclusive hiring in the formal economy is not a risk. In fact, it can drive growth and shared prosperity.

Despite the fact that South Africa’s growth has stalled in the past few years, the formal economy remains a critical engine of economic growth. We have to continue to rely on this engine to drive development and growth for the country. The past few labour market cycles have seen increased jobs in the finance, community / social services, and agriculture sectors, which continue to be priority growth sectors for Harambee and the Presidential Youth Employment Intervention (PYEI). Furthermore, Global Business Services (GBS) continues to buck the trend and create jobs. Between 2018-2022, 81,234 GBS jobs servicing the international market from South Africa were created, generating export revenue of $1.3 billion for the country. This sector continues to employ a majority of women (over 63%) and youth (89%) year on year suggesting that with collaboration and coordination, inclusion and growth do not have to be at odds.

As we work across even more sectors and build a longitudinal dataset, we have noted that the sectors like GBS that are growing are those betting on inclusion. Inclusive hiring – known in the GBS industry as impact sourcing – is just good business strategy. Organisations have seen the effectiveness and retention of “impact workers” exceeding that of workers hired through regular pathways, with corresponding reductions in absenteeism and upticks in first call resolution and net promoter scores (NPS)—both critical metrics for productivity and performance in the GBS sector.

An example is Harambee’s partnership with Webhelp, a global impact sourcing business with over 120,000 staff. Since 2019, Webhelp has worked with Harambee to source over 4,000 impact workers for their operations in South Africa, servicing international clients, including the UK’s Shop Direct. Webhelp’s own analysis suggests positive business results from their impact sourcing strategy. Despite the supposed risk of an additional upfront investment including supporting work-place readiness for impact workers, the payoffs have been significant. Through the company’s analysis impact workers have shown an 80% retention rate, compared to 50% for regular workers – resulting in a >46% cost savings in recruitment. To date, the Webhelp-Harambee partnership has positively impacted 130 families and 520 lives in the Shop Direct campaign.

The GBS industry has also benefited from significant government investment in the form of incentives for new jobs created, which includes a target of 20% for inclusive hiring. In 2022 the sector hired 30% of all new hires inclusively. With focused attention and support from the government, inclusive hiring is not just “de-risked” but can become a strategy that drives growth. It makes good business sense to bet on excluded youth. But a few employers undertaking inclusive hiring cannot solve the sheer size of the challenge. We need hundreds more employers like Webhelp to bet on young people. By joining platforms such as SA Youth, and embedding the practices of inclusive hiring, we can drive costs down and expect the margin of return to formal sector employers to continue to grow.

Lastly, we need to use both a lens of social as well as financial returns and a time horizon of generations. With this lens, all jobs and all job-seekers are not created equal. A young person who becomes the first person in their family to secure formal sector employment creates intergenerational lift, and addresses the significant stigmas and productivity losses of youth being excluded in the labour market. Our data shows that the majority of youth in our network represent those most excluded from the labour market based on factors such as gender, disability, education and backgrounds that depend on household grants. In the absence of significant macroeconomic shifts, supporting formerly excluded youth into earning opportunities represents a vital pathway out of grant dependency and an opportunity to shift the needle on intergenerational poverty.

Inclusive hiring, while a good bet for business, is also an important lever enabling growth and shared prosperity.

Figure 1: Inclusive hiring in the formal economy is not a risk. In fact, it can drive growth and shared prosperity.

Small medium micro-enterprises (SMMEs) account for at least a third of South Africa’s GDP, and yet the sector remains surprisingly small and relatively impenetrable to new labour market entrants. Our data has shown that supporting young people in informal livelihoods increases their skills and chances of securing formal sector employment. But realising these benefits remains a high risk bet for many. This requires capital to invest in stock and/or equipment, licenses and permits, or highly variable running costs such as mobile data and fuel, with the prospect of tiny margins and intense competition. Few have any savings or means to bridge a temporary setback.

New models in the informal economy show signs of changing that. Since the pandemic, South Africa’s delivery driver industry has grown. But it is plagued with barriers to entry such as licensing difficulties, challenges in owning or accessing financing for vehicles, and unpredictable incomes with low margins. This makes it difficult for many young South Africans to start and stay earning a resilient income. Harambee’s partner, Green Riders, was able to address these challenges by identifying and absorbing some of the risk for young people. Green Riders addressed the primary barrier to entry by replacing traditional motorbikes with “e-bikes”, eliminating the need for expensive and time-consuming license acquisition (ranging in costs of between R4,000-R12,000), and defraying fuel costs by opting for an electric vehicle. Since late 2022, our partnership with Green Riders has seen 500 youth being pathwayed into opportunities, enabling them to earn on average of R5,700 per month. This is significantly more than would have otherwise been possible had an intermediary not stepped in to de-risk the opportunity through providing contracts, market efficiencies, and “job” security.

Another challenge young people in the informal economy face is digital exclusion and information asymmetry: many operate their hustle with limited access to, and low visibility of, market dynamics, curtailing their ability to price labour and goods optimally. Harambee’s data from 2021-22 suggests that self-employed people engage in innovative ways to make their own money but are at the mercy of limited information on market dynamics. The result has been low incomes of R700 per month and sunstantial great variation between activities with the selling of “goods” being dramatically less profitable. Further, women earned significantly less than their male counterparts. Organisations such as Qwili are great examples of partners who make it easier for young people to make money without taking on unnecessary risk.

Qwili, provides a “spaza shop on your mobile”, allowing micro and small merchants to facilitate the sale of goods and value-added services (e.g. electricity and DSTV licenses). Thus far, Qwili has 220,000+ customers, 6,600+ daily transactions, and over 4,800 sales agents servicing the last mile in many of South Africa’s townships. Qwili enables the digitally excluded and unbanked to deliver goods with greater convenience, particularly in formerly offline communities. Since our partnership began, we have pathwayed nearly 250 youth into this type of earning opportunity. One example is Charmaine Mohale, who was able to access the Qwili opportunity despite not having options for childcare for her 15 month old baby. She is now one of Qwili’s top sellers, making over R62,000 in total sales across a 3-month period, from the convenience of her home.

Tyme Bank, an “all-digital retail bank” which recently crossed 7 million customers in South Africa, took a bet on hiring formerly excluded youth as digital sales ambassadors. Eighty percent of the 7 million sign-ups for this innovative bank have been in-store, suggesting that Tyme’s digital ambassadors – excluded youth pathwayed through SA Youth – have helped drive their growth and success. Since Harambee’s partnership with Tyme Bank began, we have pathwayed over 5,200 youth into earning opportunities, enabling them to earn on average R4,500 per month.

Partners like Green Riders, Qwili and Tyme Bank are helping to lower and rebalance risk within the informal economy, and demonstrate proof points that by betting on young people in the right way, inclusion can actually drive business growth.

Figure 2: If intermediaries can absorb some risk, the informal economy becomes easier to enter and less precarious

We need to widen our lens on what constitutes “returns,” to fully size the impact of public employment programmes.

In the absence of a job-rich economy, work experience may be too important to leave to the private sector alone. In particular, in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis and the pandemic, inclusive job-search platforms, public employment programmes, and well-implemented social protection programmes serve a very clear purpose. These programmes can reduce the risks and costs of job-searching, provide young people with something purposeful to do, and keep them engaged in a labour market that doesn’t otherwise hold promise. And looking at data from across these programmes, we see other effects too, indicating that the effective use of public funds in this way can actually stimulate job search and enterprise activity.

The Presidential Employment Stimulus programme was launched as part of government’s response to the negative impact of COVID-19 on employment, and has been a proof point in showing how effective even short-term employment programmes can be in offering hope and engaging young people who would have otherwise been discouraged. Prof. Ricardo Hausman of Harvard University’s Growth Lab says that “the inequality that matters is the inequality of inclusion (networks, connections, infrastructure) – leading to inequality of productivity”. By keeping young people engaged, productive, and hopeful, these programmes directly address this issue of productivity.

Looking back on this programme, we observe a story of successful inclusive hiring and engagement at incredible scale: over two million young people applied, with almost half of those getting the job. The jobs paid minimum wage to everyone and were distributed disproportionally to those who otherwise struggle to find employment -— women, those from poorly resourced schools, and those living in areas with sky-high unemployment. The programme design has evolved to ensure participants learn valuable skills that can be transferred to other environments. We are now learning about their transitions and pathways after the programme. One example is Timothy Maluleke, who was a DBE teaching assistant at the Katlehong Engineering School of Specialisation. After 12 months on the job, Timothy was made aware of an opportunity on the SA Youth platform to make his own money using Qwili. He met Charmaine through the DBE teaching assistant programme, and he encouraged her to apply for the Qwili opportunity – where they are both now top earners.

Additional research addresses concerns that social grant spending might further increase dependency. On the contrary, research by Köhler & Bhorat 2021, shows that the social relief of distress grant actually increased work-seeking behaviour. This suggests that these programmes, if well run, can support job-seeking and stimulate engagement even when there are not enough jobs to go round, particularly for those most excluded. Our own data suggests that higher engagement during job search itself is half the battle won – and that this can dramatically improve placement success. Data from the 2023 Q1 Quarterly Labour Force Survey suggests that over the past few quarters, there has been a gradual rise in the numbers of those who have been actively searching for work. This has surpassed pre-COVID numbers and is a promising sign of a depressed labour market, encouraging individuals who would not have otherwise looked for work.

It is clear that even when there are too few jobs, investing in making job search easier and creating employment options such as the DBE programme, has returns beyond the period of the job itself. Recognising this could shift public spending toward more effective youth employment interventions.

Youth month is typically when we celebrate the potential and resilience of all our young people. Despite the long-term data showing how the growth of the youth employment challenge has outpaced the growth of our solutions, the greatest risk now is that we slow down. We must not continue to demand more resilience from our young people than we do from the systems that fail them.

The return on our collective investment should not just be assessed by the earnings for young people, the productivity gains for employers or the economic ripples across communities that they have generated. Nor even by the hope they have restored to millions of young people. The returns should also be assessed in the sum of what we’ve learned about how to reduce risk and optimise the social and economic returns of inclusive hiring. This learning is what will power our shared prosperity and growth. The need may never have been greater, but the case for sustained investment has also never been stronger.

Figure 3: Public programmes activate and engage NEETs in some form of productive work.

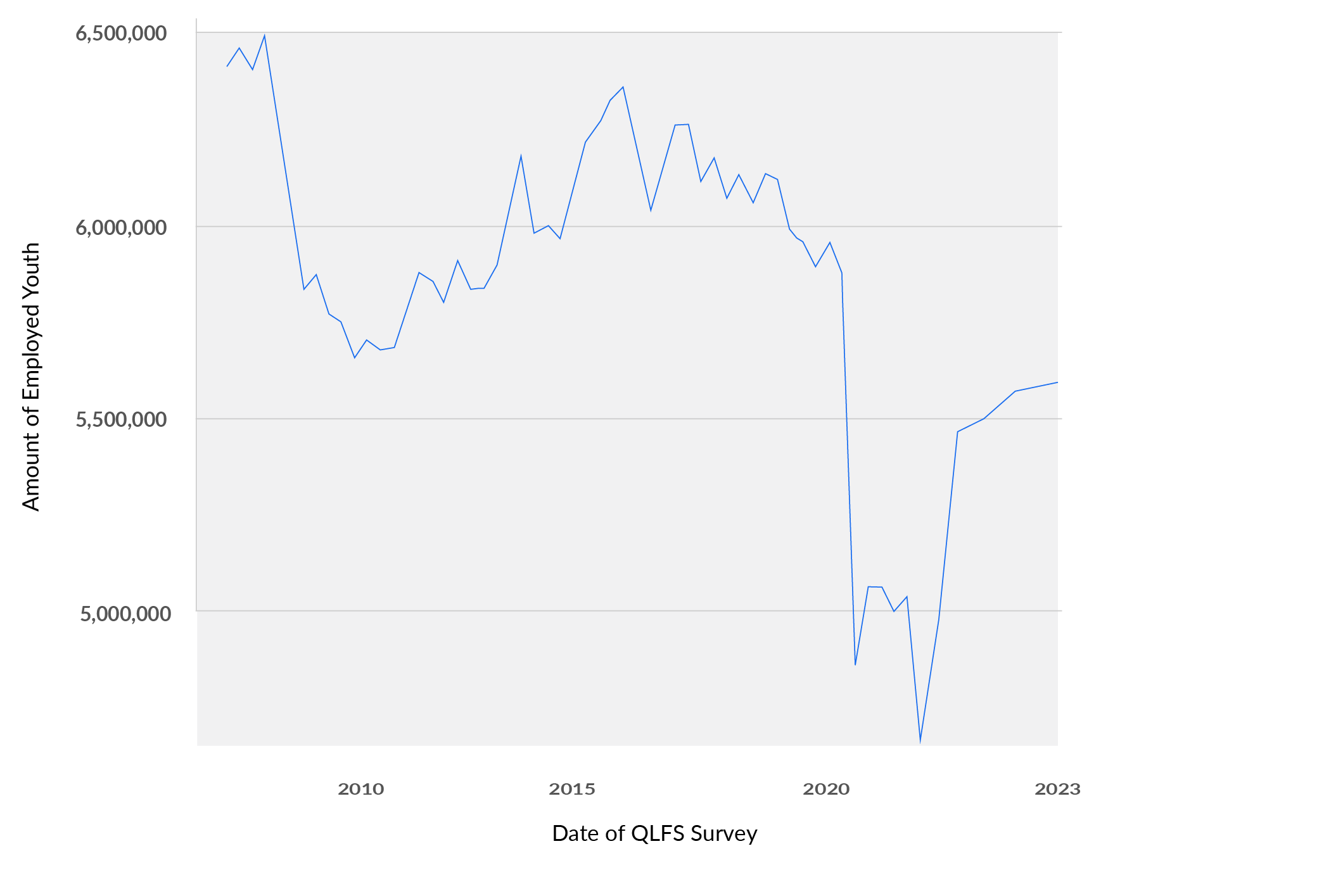

The latest QLFS data suggests that youth employment has started to climb back up. A total of 5.6 million young people are currently employed, roughly the same number as 2020 Q1 (thus, immediately pre-Covid), and about 500,000 higher than one year ago—encouraging positive developments. However, the workforce itself has increased over the period and the proportion working is at 44% (compared to 41% one year ago and 50% five-years ago). Below is a graph of the proportion of young people employed, and although the proportion has recovered, it has recovered to the broader long-term trend which is downwards. Male employment seems to be increasing slightly but female employment has plateaued. Many of the other indicators (like permanent jobs, length of employment) seem to be back on long-term trends.