BREAKING

BARRIERS

Quarterly Report

June 2024

The only long-term, sustainable solution to our youth unemployment crisis—deep economic regeneration—remains frustratingly elusive for South Africa’s 17.5 million young people. While the latest QLFS figures suggest that youth employment has improved over the past year, we are yet to return to pre-Covid levels of employment, let alone see the levels of job-rich growth our economy needs. As our youth population grows faster than the jobs available, many data points are heading in the wrong direction: every second young South African aged 18-34 is Not in Education, Employment, or Training (NEET). Among African women under 35 who eventually get a job, the average age at which they get that first job has increased from 24 years to 25 years (QLFS 2014 and 2024). Furthermore, according to Harambee’s own data, job stability has decreased, with average job duration dropping from 10 months to 6 months after Covid-19, across public employment programmes, formal sector and self-employment. Self-generated hustles are even more precarious, with an average duration of only 3 months.

Against this backdrop, some argue that until we build the economy we want—an economy of plentiful, secure, accessible entry-level jobs—there’s little point to investing in work interventions. But a deeper look at the data shows that view is not only wrong, but dangerous for today’s youth. It leads to what Prof. Ariane de Lannoy refers to as waithood: “…an anthropological concept expressing that young people really want to move towards independent adulthood, but there is a stage where they simply get stuck. And this stuckness is not static sitting and waiting, there is a lot happening: young people are hustling to create a livelihood, or reconnecting to education or to the labour market or making decisions for themselves”. It is vital we keep young people moving, strategically and with support, within the economy we have—not letting them stagnate waiting for the economy we want.

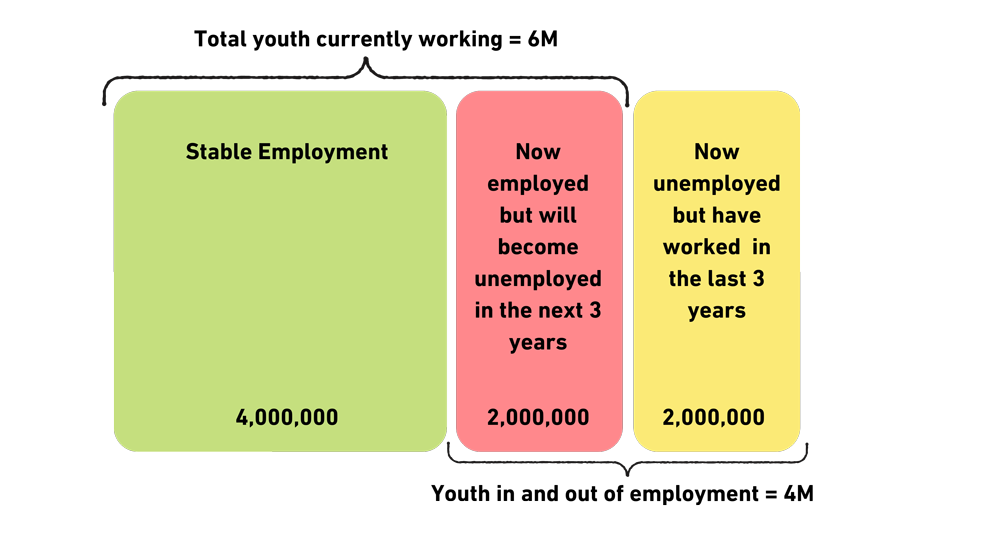

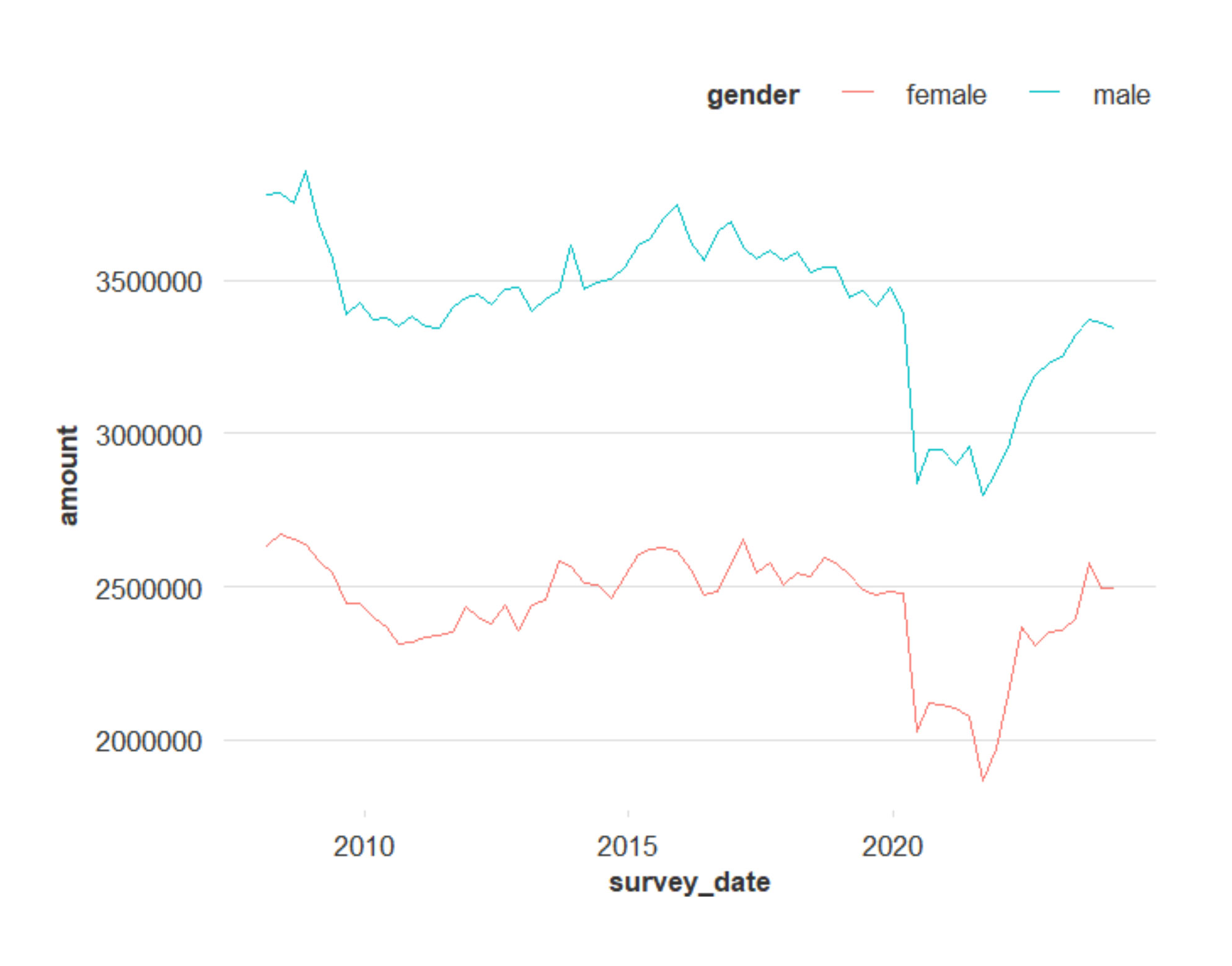

Evidence suggests young people are working even harder for any chance to work: Since 2014, the number of youth actively searching for work has increased by 6 percentage points. Their energy is helping to drive increased zig-zagging within the economy. We see this reflected in SA Youth data: of 3.8M youth, only 10-15% stay employed and are sustainably employed, with 30-40% churning in and out of work, between public employment programmes, private sector and short term income earning opportunities. This is corroborated by QLFS: though 6 million young people are ‘currently working’, a total of 8 million are moving in and out of employment in the short to medium term—see chart.

In the absence of enough stable, long-term employment to go round, this zig-zagging and circulation is a good thing. We know from our experience that getting work experience early can positively impact income mobility, whilst delays have the opposite impact. Working also provides essential non-income related benefits, such as improved mental health and providing structure to people’s lives.1 Every part of the economy has a role to play, acting as a stepping stone, signpost or safety harness at different times in a young person’s journey.

The formal sector is the “top layer” of our employment mix: the source of stable, well-paying work that keeps young people motivated to build their employability. Transitions into the formal sector from other work opportunities are associated with income mobility. They tend to pay better and have a longer duration than other work opportunities. Our research has shown that if a young person has been employed for a year, the probability of them having a job in 1 years’ time is double that of someone who has worked for only 30 days. But the vast majority of entry level contracts are for fixed, short durations as employers are using structured programmes (learnerships, Youth Employment Service, fixed term contracts) as an entry-level recruitment strategy. So in the formal economy, our mandate is to ensure that these roles are accessible to as many young people as possible, and set up to give them the best chance of success – vs. it being a lottery ticket to a lucky few.

Public employment programmes are the next layer, and in South Africa, it is a vital one. In most upper-middle-income countries (UMIC) with small formal sectors, the informal economy is large, diverse and offers decent earning potential. That is not the case here.2 Without a well-developed informal sector, government-funded public works programmes offer young people essential, first-time work and income generation opportunities, and keep them engaged in the labour force.3 The work itself is valuable: research points .4to the impact of productivity gains in these government-funded short term opportunities. Our data shows that these programmes, if well administered, address the most excluded – those who would not have found work, even if growth had been job-rich.

The informal economy is sometimes the only gateway to work for young people who are geographically cut off from other opportunities. It acts as an important fall-back or income bridge for those yet to land a formal sector or public works contract, or coming to the end of one. And, with increasing digitisation of the economy, it can open doors to real entrepreneurship.

In the absence of an economy that grows, we can create an economy that moves. By increasing upward momentum between these layers, we can make sure the vast majority of youth will work at least once before the age of 30. Momentum will come from:

- Improving access to the jobs of today – i.e. prioritise inclusive hiring

- Enabling short term work experiences to be more effective and available to young people.

- Making opportunities visible and accessible, improving transitions between them through pathway management (what SA Youth sets out to do)

For each of these levers, our insights can help direct why, where and how to invest.

KEY INSIGHTS FOR

THIS QUARTER

1. Improve access to the jobs of today – prioritise inclusive hiring.

Our Insight: Across sectors, employers who are prepared to redefine what a “good employee” looks like reap the rewards of inclusive hiring.

Educational achievement doesn’t tell the full story of potential. Many young unemployed people in South Africa did not have the chance to perform at their fullest potential at school, whether due to poor resourcing or low quality or the hard set of life circumstances they faced in childhood. Even with good matric results, education in a 1 to 3 school decreases the likelihood of being employed: all else equal, there is a 5 percentage point quintile penalty between young people in quintile 1 and 5.

In response, Harambee has developed Behavioural and Practical Problem Solving screeners to identify the 20% of young people in our network with high potential but poor matric results. Through these screeners, we have been able to double the proportion of applicants who we can confidently recommend for opportunities, but who have a traditionally weak profile, from 12% to 25%.

Likewise, prior experience appears to be a poor proxy for potential, in some sectors at least. Employers have widely different propensities to hire youth without previous experience. Those employers most likely to hire first-time work seekers are in education, government, and the food sector, while those more likely to look for experience when hiring are in finance, insurance, and other professional services.

SA Youth data suggests that, 57.9% of self-reported opportunities at McDonalds are individuals with no previous experience recorded, compared to 39.1% at Food Lovers Market .5

Another food sector employer and Harambee partner, Nando’s South Africa, has committed to using the SA Youth platform to hire entry-level talent for all their corporate stores. Nando’s recruits young people by catchment area to ensure that each employee lives only one taxi ride away from their workplace, and provides dedicated transport for staff working late shifts. Between March 2023 and May 2024, 77% of Nando’s total entry-level placements came from the SA Youth network. With a very high internal promotion rate, the company aims not only to employ young South Africans but also to nurture them into future managers.

If there is any doubt that inclusive hiring and growth can go hand in hand, the Global Business Services (GBS) sector dispels it. The GBS sector is both growing and blazing a trail in inclusive hiring, creating over over 100,000 work opportunities in South Africa since 2019,6 with our research indicating that the average entry-level job pays approximately 40% more than the average private sector job in the country. Organisations such as Shadow Careers and Merchants have leveraged government investment to create an additional 5,000 jobs for previously unemployed youth transitioning into the sector through work readiness interventions.

1 Knabe, A., Schob, R., Weimann, J. (2017). The subjective well-being of workfare participants: insights from a day reconstruction survey. Applied Economics. 49(13): 1131-1325.

2 World Bank (2023). Supporting informal employment in South Africa. November. [Powerpoint Presentation]

3 Motala, S., Mncanga, B., Ngandu, S., Chetty, K., Harvey, J. (2024). A Study to Evaluate the Effectiveness of National Policies aimed at Facilitating the entry of young people into good quality employment. [Powerpoint Presentation].

4 Philip, K., Kie-Song, L., Tsukamoto, M., Overbeck, A. (2019). Employment Matters too much to society to leave it alone: The role of Public Employment Programmes as part of a Social Contract for the future of work. Presentation for 6th conference of the Regulating for Decent Work Network, ILO, Geneva.

2. Enable short term work experiences to be more effective and available to young people.

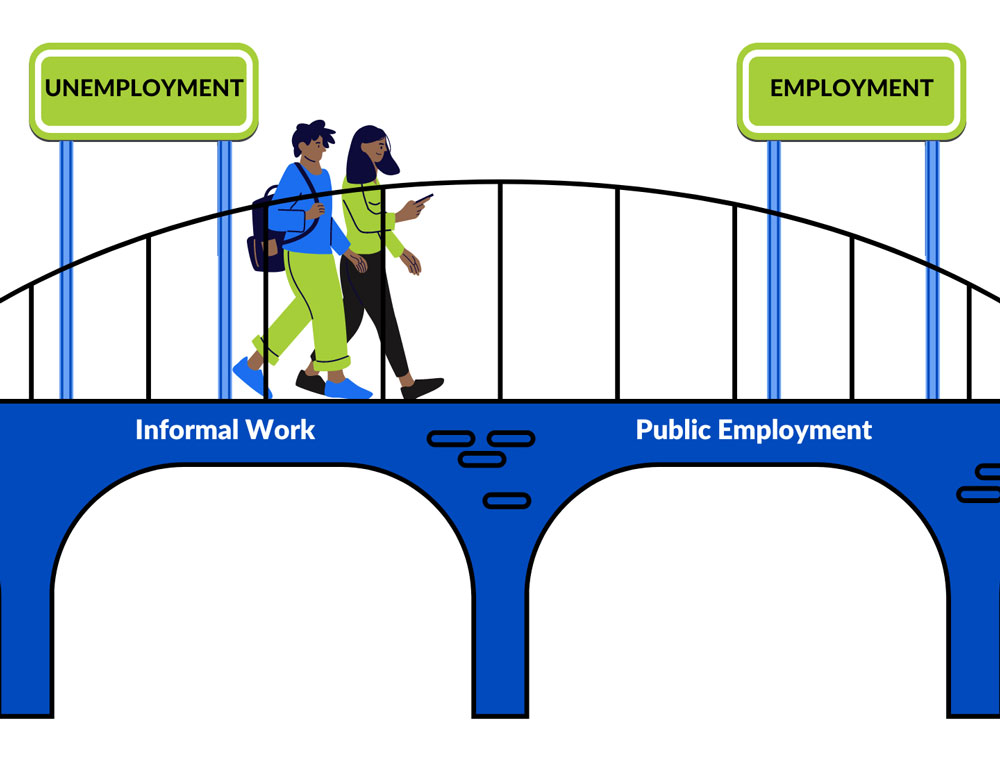

Our insight: Public employment and informal work are vital bridges (and in many parts of South Africa, the only bridges) to work. Improvements to these programmes make them function better for work-seekers.

Decades of research has shown that income-earning work is important to societies, providing individuals with a means to contribute to society, support themselves and their families, build self-worth, networks and skills.7 In the absence of formal sector jobs, public employment programmes provide many of these benefits, particularly in rural areas which are often ‘jobs deserts’. In our sample of 164,625 young people with more than one work opportunity recorded, half had their second work opportunity in a public employment programme. Youth in rural areas are 4x more likely to engage in public employment programmes than in the formal sector, in comparison to youth in urban areas who are only 1.5x more likely to do so.

Our research has shown that public employment programmes provide income on par or just below minimum wage (around R4,000+ per month for full time work) to many youth who were not previously earning any income, with opportunities lasting an average of 6 months. The fixed earnings of public employment programmes provide earning certainty (albeit, over a short period of time), whereas other options young people turn to during waithood, such as self-employment, tend to have little to no certainty.

We know that public employment programme participants who transition to the formal sector engage more heavily in certain industries relative to all youth in the sample. But overall, this experience tends to translate less often into formal sector roles than other experiences. While this likely reflects the geography of public employment programme participants, more work can be done to understand how to better support these youth to translate their experiences into other full-time work opportunities. One option to explore is whether reaching out to youth while they are engaged in a public employment programme, offering them individualised coaching support, connecting them to relevant services and ensuring that all their documents are up-to-date could help strengthen their employability going forward. Findings of the Basic Package of Support pilot phase indicate significant and positive shifts in young people’s well-being, orientation towards, and uptake of education, training and employment opportunities after just three personalised coaching sessions.

Self-employment opportunities tend to be less economically secure than formal sector work or public employment programmes. Transitioning to a self-employment opportunity (from the formal sector or a public employment programme) is associated with economic fragility: only 12% of young people in our sample who transitioned to a self-employment opportunity earned a monthly income, (as opposed to inconsistent piece work) and even fewer earned an income that was better than their first role. Even so, self-employment remains an important element of an economy that moves. Firstly, young people tell us it is a bridge until they can secure a role in the formal sector or a public employment programme. SA Youth data confirms this: if their first opportunity is in a public employment programme or the formal sector, a young person tends to move on within the sector. By contrast, three quarters of those in self-employment leave it for a work opportunity in one of the other two sectors.

But self-employment has a bigger role to play, too. A recent report on township economies estimates the potential market value to South Africa’s economy from its 500 major townships at ZAR 900 billion. This is potential that is largely unrealised: thanks to the proximity and spatial exclusion of townships from central business districts, most of their businesses remain small-scale and essentially survivalist, tending to circulate local resources rather than produce tradable goods and services that serve wider markets, create decent work opportunities, and generate higher incomes.

Not all forms of self-employment are equally risky or unpredictable. Partner opportunities that provide the scaffolding of access to markets, base salaries and business mentorship yield more resilient and durable earnings. One such partner is GoBuddy, a green e-commerce delivery service operator. GoBuddy has registered 3,140 individuals on its platform, of which it estimates that 90% are from the SA Youth network. Our data suggests that salaries for these types of partner opportunities range between R3,000 – R5,000 per month with an average duration of 12 months. This is in comparison to the R700-900 earned and 4.9 month duration experienced with more survivalist self-employment activities.

5 Based on SA Youth data, June 2024.

6 United Nations (n.d.) Young People’s Potential, the Key to Africa’s Sustainable Development. Retrieved here.

7 See Bhanot, S., Han, J., Jang, C. (2018). Workfare, wellbeing and consumption: Evidence from a field experiment with Kenya’s urban poor. Journal of Economic Behaviour and Organization. 149: 372-388; Knabe, A., Schob, R., Weimann, J. (2017). The subjective well-being of workfare participants: insights from a day reconstruction survey. Applied Economics. 49(13): 1131-1325; Philip, K., Kie-Song, L., Tsukamoto, M., Overbeck, A. (2019). Employment Matters too much to society to leave it alone: The role of Public Employment Programmes as part of a Social Contract for the future of work. Presentation for 6th conference of the Regulating for Decent Work Network, ILO, Geneva.

3. Make opportunities visible and accessible, improving transitions between them through pathway management

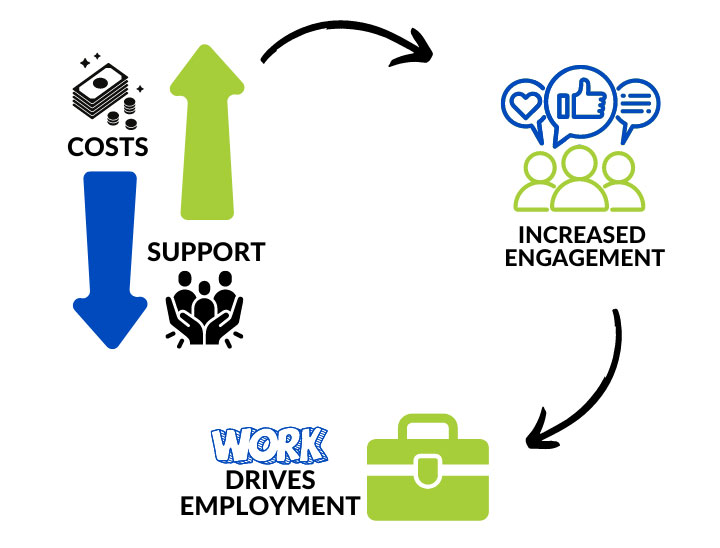

Our insight: engagement drives employment; lowering costs and increasing support drives engagement.

Millions of young South Africans are already experiencing waithood. Of the approximately 9 million youth not in employment, education or training (NEET), 4 million have never worked but want to. It is vital to keep these young people engaged, as well as the up to 40% of income-earning youth who churn in and out of work. Those who lose hope risk becoming permanently, even dangerously, disengaged.

Research shows that cost is a barrier to engagement. Work-seeking imposes high costs on young people, from childcare to transport and data. The Beyond the Cost report series showed that internet costs (up to R441 per month), transport costs (R700) and application fees (R328), can add to as much as R1,467 in monthly work-seeking costs for the young South Africans who participated in their study. Our research shows these costs are regressive: those who earn in the lowest quartile spend a higher proportion of their earnings on them, compared to those earning in higher quartiles. Although the SA Youth platform is zero-rated, if a company requires the work-seeker to click through to another site to apply for an opportunity, they will need data to do so. In fact, 41% of respondents in our network cited a lack of data as the reason they were not applying for jobs. There is more work to be done to reduce work-seeking costs system-wide.

While work-seeking costs inhibit engagement, good quality support and active pathway management increases it dramatically—by over 100% in our network—which in turn improves work outcomes. Handling an average of 65,000 calls with young work-seekers every month, our call centre is a rich source of insight into what makes the difference: a conversation with a human that provides pragmatic and personalised guidance to a young person. Personalised, so they feel like they and their work-seeking journey matter. Pragmatic, so they leave the call with concrete next steps and clear goals to follow through on, such as an SMS link to update a CV, or access to the Coach Me chatbot. As Anele*, a 29-year-old work-seeker from Gauteng, said to her call centre guide, “You don’t have any idea how much I needed to hear this. I know I have capabilities, but I always limit myself… I really appreciate this conversation and I’m going to do more to fix all these things”.

A job-rich economy will be years, if not decades, in the making. But our research shows that with outcomes-driven interventions rooted in data that address the barriers young people face to labour market entry and provide access to opportunities for work, we can improve the economy we have and sow seeds of growth at the same time. Through the prioritisation of inclusive hiring, availability of short term work experiences and accessibility of opportunities through pathway management, we can get young people moving and earning. For young South Africans, the wait has been long enough.

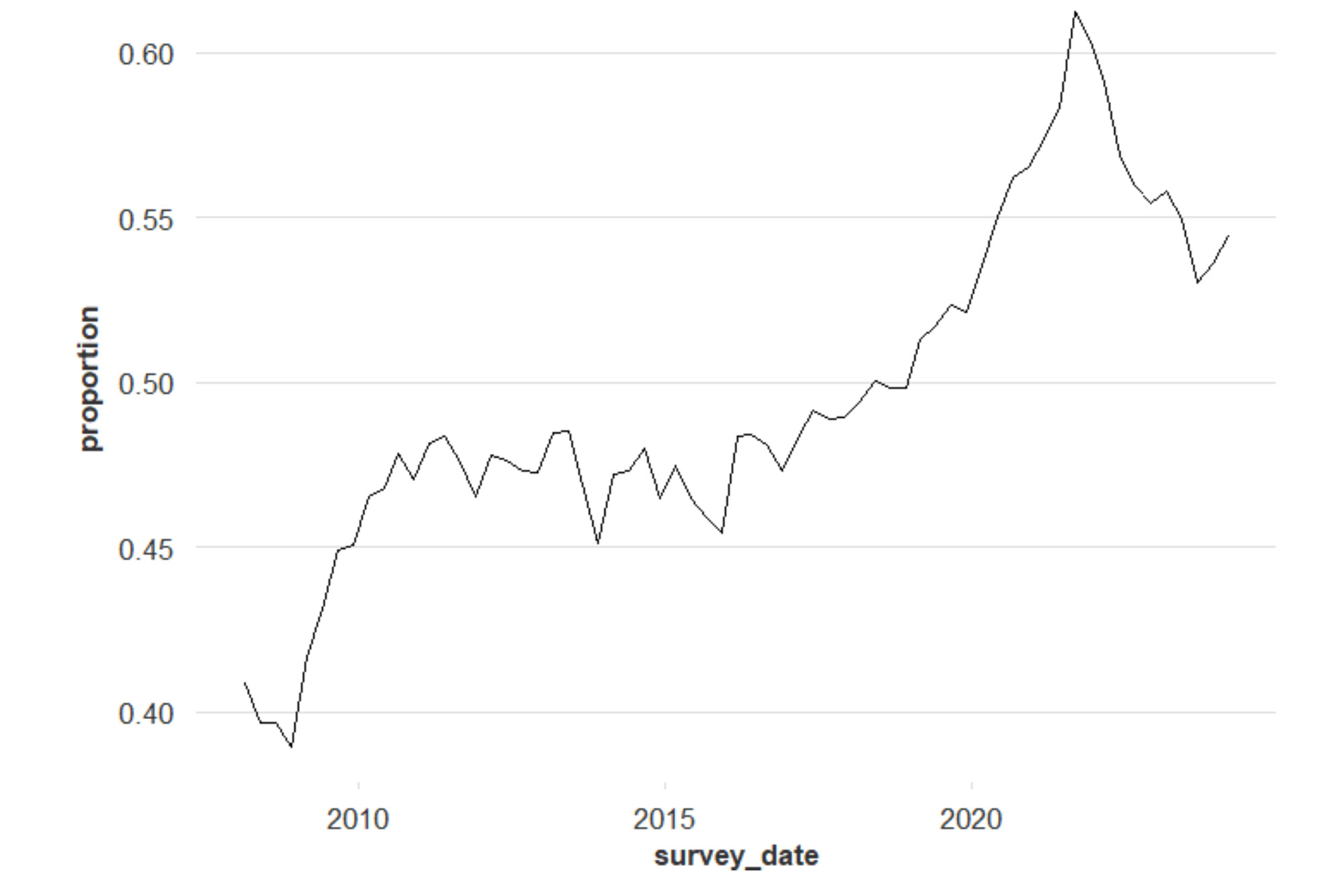

Quarterly Labour Force Survey Release – 14 May 2024

For 18-34 year olds in South Africa, the Q1 2024 QLFS results indicate that youth unemployment rose to 54.4%, driven by the seasonal dip in employment following the festive season. The number of those in employment also dipped, with approximately 14,000 less individuals in employment compared to the previous quarter; however, year-on-year, the total number in employment is 233,000 more.

For women, employment levels have returned to what was experienced pre-pandemic, unlike men, who seem to be stagnating at lower levels. This may be as a result of some lower-skilled jobs that were predominantly held by men vanishing permanently, creating a new ‘structural’ level of unemployment. Examples of this include the 100,000 fewer young men working in low complexity construction jobs now compared to 2019, as well as, jobs lost over this period doing manual labour within private households and in community. Some gains, however, have been made in the approximately 50,000 jobs in business services, enabled by a rise in security related and digital jobs. Young women also saw a reduction in certain elementary jobs within the manufacturing sector and private households (e.g. 30,000 domestic jobs lost) during the pandemic but education, health and retail job-gains have helped offset this. Service roles are also more traditionally suited to women (braiding, cashier, service agents, teaching, care work) and seem to have come out more resilient than manual work traditionally completed by men.

Amongst NEETs aged 18-34 years, the results reflect a marginal increase in the total number to 8.9 million, contributing to 50.6% of the youth population. Of the 8.9 million, approximately 6.5 million are broadly in unemployment whilst the remaining 2.4 million are young people who are not economically active and have no desire to work – many due to care responsibilities.

Expanded Youth Unemployment Rate

Youth Employment by Gender

NEED MORE INFORMATION?

WANT AN OFFLINE VERSION?

Stay Connected

Stay Connected