SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

13 August 2025

This Women’s Month, we spotlight the economic power of inclusion. The fundamental freedom to work and earn is often frustratingly elusive for women. This inequity is reason enough to pay close attention to the data on women’s participation in the labour market, but there is also a compelling economic reason to do so: growing our labour market equitably benefits everyone.

Raising the employment prospects of women is not a zero-sum game that redistributes employment away from men. It is a powerful economic multiplier, one that could increase global gross domestic product by 20%, the World Bank calculates. Closing gender gaps in employment and entrepreneurship could also boost average wealth by 14% because including women in the labour market unlocks potential and raises productivity. Gender inclusion brings complementary skills, distinct insights, imagination and perspectives to the workplace, all of which enhance innovation. Inclusive teams that embrace gender diversity are also more likely to challenge entrenched assumptions, explore unconventional ideas, and generate breakthrough solutions.

The social benefits of women’s participation in the workforce are significant. In South Africa, economically empowered women have been shown to invest more in their families and communities, improving health, education, and reducing child mortality. These intergenerational benefits ripple outward, strengthening social cohesion and national development.

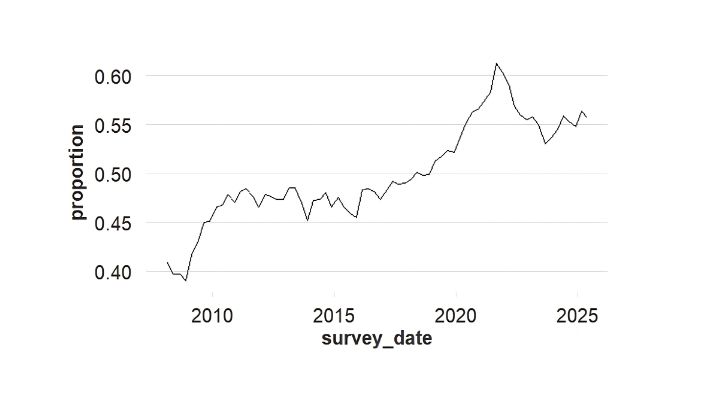

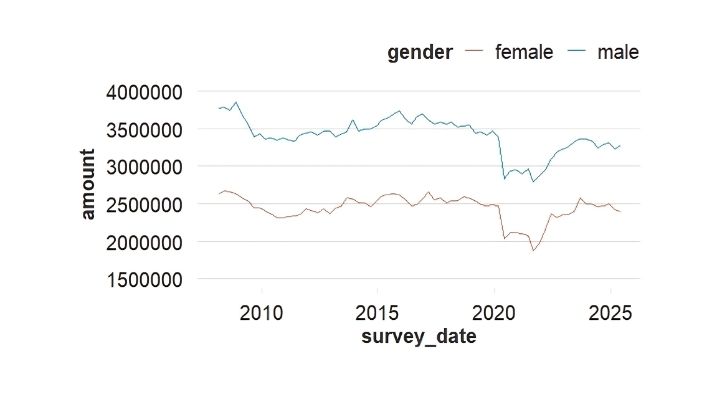

Such benefits explain why, in 2014, the G20 countries made a historic commitment to reduce the labour force participation gap by 25% by 2025, known as the ‘Brisbane Goal’. A decade on, South Africa is one of nine G20 countries to have achieved this, adding over one million women to the labour market between 2012 and 2024. South Africa is also one of the G20 countries to see a large reduction in the disparity in earnings between men and women, which was achieved by tying the minimum wage to increases in inflation, lifting the earnings floor and protecting minimum wage workers. This has had a significant effect on workers in the care economy, including domestic workers, who are disproportionately female and often earn minimum wage. But gender disparities persist. Women continue to face systemic barriers to entering and staying in the labour market, with the labour force participation rate for women at 54,9%% compared to 65,6% for men (QLFS Q2, 2025).

Lack of education is not the problem; young women are more educated than their male peers: 116 women hold a matric or higher qualification for every 100 men under 35, and approximately 50% more women have degree-equivalent qualifications. The problem is that women face far bigger barriers to entering the labour market in the first place. They do more unpaid care work, have less mobility, navigate more safety issues, and struggle against biases that exclude them from higher-paid opportunities. Understanding these barriers and how they intersect is the first step in closing the gender employment gap.

The foremost of these barriers is unpaid care. Women spend far more time than men doing housework, childcare, and other care activities, which limits their time to engage in paid activities. The International Labour Organisation estimates that across the G20 countries, women still complete about twice as much unpaid domestic and care work as men. In South Africa, for every man staying out of the labour force due to homemaking responsibilities, more than eight women are in the same position.

Women’s unequal care demands are exacerbated by safety concerns and reduced mobility. Women are disproportionately affected by gender-based violence when using public transport or walking to and from stations, especially at night. This influences women’s decisions around bus routes, affordability, and access, often forcing them to rely on e-hailing or taxis, which are more expensive.

Even when women overcome these barriers and enter the working world, they face penalties once they get there. Gender bias and occupational segmentation (the uneven distribution of demographic groups across occupations) exclude them from higher-paying roles, and precarious contracts and lack of support structures push them out of the formal economy quicker than men. Historical trends indicate men consistently earn more, with median monthly earnings for women clocking at 25% lower than for men in 2022. Even in sectors where women are overrepresented, such as care, retail, education and community-related work, roles are often informal, underpaid, and lack protections.

So how do we get more women working? By designing employment interventions that are equitable by intent and inclusive by impact. Furthermore, many of the structural barriers that keep women out of the workforce also work against other historically excluded groups. This is why Vision 2030, the national strategy for youth employment, was developed with an equity lens that benefits all. In this issue of Breaking Barriers, we spotlight how employers, policy-makers and others can ensure their investments work harder to benefit women, which means benefiting everyone.

Sectors such as Tourism and Global Business Services (GBS) are already experiencing considerable growth thanks, in part, to the inclusion of women. In GBS, 6,290 jobs were created in the last quarter, 92% of which were filled by youth and 68% by young women. Against the sector masterplan target of 500,000 GBS jobs by 2030, this sustained trend could translate into 335,000 jobs for women, over the next five years. The potential benefits go beyond these jobs: work experience in the GBS sector is a particularly effective enabler for onward access and retention, compared to other jobs. Harambee’s data shows that young people working in GBS are more likely to report getting a second opportunity in the formal economy than those with jobs in other industries. The SA Youth platform connects young people to earning and learning opportunities and comprises of 65% young women. Of its users who logged more than one work experience in the formal economy, 74% reported getting another work experience in the formal economy, compared to 84% of young people with GBS experience. This matters because formal work is the most sought-after type of employment: it lasts longer and offers higher earnings than self-employment or public employment programmes. Harambee’s income data reflects that amongst those who stay in wage employment, approximately 57% see a real earnings increase over 6 months, with an anticipated increase of 5-10% when staying in the same job. The benefits of getting and staying in formal employment are apparent, and GBS jobs provide a gateway for women to access, contribute to, and stay in the formal economy.

Tourism is another dynamic and youth-friendly sector driven by women. In 2024, it contributed 8.8% to GDP and supported nearly 1.7 million jobs, of which 70% already go to women. Here, the whole value chain has great potential as an employment gateway for youth. This was demonstrated through the Tourism Department’s Tourism Monitors programme, in partnership with SA Youth/ Harambee. It placed 2,000 young people across more than 100 sites between 2023 and 2024. With 77% female participation and 75% of youth coming from under-resourced communities, the programme is setting a benchmark for gender inclusion in the sector. Recruitment has begun for a 2025 cohort on the SA Youth platform.

Though unpaid care work acts as an inhibitor on women working, the Care Economy itself is another major engine for growth that is powered by women. Made up of roles in Education, Early Childhood Development (ECD), Domestic Work, Healthcare and Long-term Care, it contributes an estimated 15.9% towards total employment (QLFS Q4 2024), and has the potential to generate 3.7 million jobs in ECD and Long-term Care alone by 2030. The ILO estimates that every dollar invested in care within South Africa could result in a GDP increase of 1.34 dollars. Globally, prioritising the care economy could increase women’s employment in G20 countries by 7-12% and reduce the gender pay gap by 2-20%, per World Bank estimates.

Women’s inclusion in these dynamic sectors does not come at the expense of men’s. Rather, including women drives sector growth, which benefits everyone. Failing to prioritise inclusion, on the other hand, could widen disparities, limit growth and compromise employment targets.

In the formal economy, when women do gain a foothold, it tends to be less firm than men’s. Our research has shown that among young people who have reported more than one earning opportunity on SA Youth, men were 5% more likely to report a second opportunity in the formal sector, compared to women. We know why: women face transport and safety issues and carry a far heavier care burden than men. They fall out of the formal economy at higher rates than men, contributing to high churn.

Reducing churn and keeping women in their jobs benefits everyone, not just women: employers realise the productivity gains from retaining more of their experienced workers, and male employees benefit from better working conditions too. Solutions include flexible hours or work-from-home options, allowing employees, particularly women who are primary caregivers, to balance care responsibilities with their jobs.

Procera, a GBS employer, has taken meaningful steps to foster a more inclusive and supportive work environment. In its Collections business unit, the company has implemented shorter shifts (7am–2pm and 2pm–8pm), which contribute to improved stress management, healthier lifestyle patterns, and a reduction in overtime costs. These flexible working hours are especially beneficial for women balancing professional and personal responsibilities.

Other inclusive solutions address the commuting penalty by offering transport solutions for employees, which makes jobs easier and safer to get to, particularly for those who do shift work that straddles dark hours. This ensures employees aren’t forced to use public transport during unsafe times – a disproportionately riskier activity for women. GBS employer Sigma Connected, whose workforce comprises 65% women, provides free shuttles to their employees from key locations in the morning, and free door-to-door transport for junior employees finishing at 6pm or later. Another GBS employer, Concentrix, provides door-to-door transport from 7pm, including home pickups for 10pm shifts. Other solutions, like that offered by skilling provider Shadow Careers, give an advanced stipend to assist with travel to work in the first month. These transport solutions are available to everyone, men and women, and are particularly critical to supporting youth employment and retention, especially during the initial period of employment.

Some solutions are gender-specific at the point of delivery but have wider benefits for families and communities. Concentrix, for instance, offers 50% paid maternity leave after one year of service and menopause support policies. It has an onsite clinic and wellness centre, with qualified nurses supporting pregnancy, menstrual, and other gender-specific health needs.

Ensuring decent, equitable pay is a non-negotiable for creating an inclusive labour market. While South African law advances this principle, socioeconomic conditions and persistent burdens create barriers to achieving it. Unpaid care responsibilities, lack of mobility, and transport and safety concerns all prevent women from working the hours needed and taking up the jobs offering the most competitive salaries. Their resulting lower wages provide less incentive to stay in the workforce, especially in the face of the extra costs that women face in dressing professionally, commuting safely and backfilling their domestic and caring responsibilities.

All growth sectors can ensure that women and young people don’t get screened out at the first step of the hiring process due to a perceived lack of skills and experience ‘on paper’. Harambee continues to innovate systems that allow workseekers to signal their potential beyond traditional qualifications or work experience, which young people and women, in particular, may lack. For instance, because young women take on more domestic and family responsibilities than men, and at a younger age, they develop broad, transferable skills like budgeting, organisation, social coordination and communication. But in a traditional CV format, these are, at best, invisible. At worst, they show up as career gaps.

The recently launched ‘SA Youth Inclusive CV’ is designed to help young people signal their potential to employers in a more equitable and evidence-based way. Early evidence suggests that adding inclusive proxies to traditional ways of screening for employment increases hiring up to 38%, providing young people with an alternative signal of ability. For employers, this reduces search costs and friction for hiring youth without traditional work experience. Since its launch in June, the inclusive CV has been downloaded over 114,699 times, with 35% of young people going on to update their qualifications or experiences after download and 24% downloading it multiple times. We are already seeing that the uptake of this tool is strong among young women (71.9% of downloads are from women), and we will continue to track its use.

Inclusion is a national priority and will determine South Africa’s ability to reach the bold targets we have set for the next five years of reducing youth unemployment by 10-20%. Improving women’s inclusion, earning power and retention in the formal economy is necessary to get closer to this vision, and benefits men at the same time.

But prioritising inclusion in the formal economy won’t be enough. Sustainable pathways for women also need to be forged into the informal economy.

Recent debate in the media has raised questions about how big South Africa’s informal economy really is, and how to define it. We know that most of the informal work being done is either invisible, unpaid, in a regulatory grey area, or all of the above. We also know that it is mostly being done by women. Data from SA Youth bears this out: women on the platform are 10% more likely than men to report an informal hustle, most of which are home-based or location-based, making this a safer and more flexible work arrangement than typically found in the formal economy.

Women’s informal work includes hair and beauty, domestic work, food preparation, tutoring, room rentals, childcare and emerging gig work. Much of this work, paid or unpaid, is vastly undervalued. Care work, for example, and the skills it develops, is often overlooked in the job market because of long-standing social beliefs and gender bias about what counts as ‘real work’. Gig work is attractive to women, with its promise of greater flexibility in terms of time and geographic location, and the access it gives to previously untapped markets. But challenges remain around job security, precarious earnings, shifting market demands, and connectivity.

Targeting support to sectors like care and gig work is crucial to being able to close the gap in employment. The first step is to properly recognise the effort and skills developed in these activities. Adopting skills frameworks, such as the one in development with the University of Oxford and Tabiya, that are inclusive of women’s experience in the ‘unseen’ economy, equips all young people in informal work to better signal their value to the broader labour market. The next step is to ease regulations and red tape, beginning with simplifying licensing processes, reducing cost burdens, and recognising informal traders not as transgressors but as legitimate contributors to the economy. These changes make informal activities work better not just for women but for everyone doing them. Within the ECD sector, red tape reduction improves the quality of care for children; benefits caregivers, particularly women; and strengthens the broader economy. The sector’s potential to unlock up to 536,000 opportunities, largely for women, positions it as a cornerstone of inclusive economic growth and the Bana Pele campaign is driving this momentum. The campaign seeks to facilitate the registration of, and access to funding for, early learning programmes (ELPs). Nationally, the campaign has reached over 20,000 ELPs, enabling over 7,000 of them to reach bronze status and begin the journey to the silver/gold registration required to unlock government subsidies. With an additional R10 billion made available in the recent fiscal budget to increase the amount of the subsidy per child and ECD access to 700,000 children, this also fuels entrepreneurship by enabling practitioners to hire more staff, improve service quality, and scale their operations.

Economic development strategies that acknowledge the informal sector’s role in job creation are better positioned to embed support for it into their plans. This can include improving transport infrastructure, providing subsidies to ease operational burdens, and expanding access to finance to empower small businesses to grow. Many informal businesses start with little or no finances, despite 60% of informal businesses requiring some form of start-up capital, and among these, about 80% use their own funds.

Financial record-keeping is scarce among most informal business owners: over 70% of informal business owners keep no financial records, and around 75% do not have a business bank account, which blocks access to financial products and capital. Practical interventions to build financial skills can address this, as IMBE, a not-for-profit that supports women-owned micro-businesses in the ECD sector, is showing with its business-skilling support for ECD practitioners. This includes a digital tool that tracks finances and learner data to support income and expense management in a way that is simple and familiar to ECD practitioners, with a focus on building skills and independence beyond data collection. The data captured by this tool can create an alternative set of records to evidence the potential ‘bankability’ of ELPs, as well as offer underwriting insights for future access to credit and insurance services. It also serves as a valuable source of insight for IMBE to better support practitioners through tips, guidance and practical interventions tailored to their specific needs.

Centralising small business information enhances connectivity and relevance, and informal workers also need tailored social protection schemes that offer financial security during times of vulnerability. Together, this scaffolding can transform the informal economy into a vibrant, inclusive engine of growth. They are not women- or ECD-specific: they can be replicated in other sectors, including those where the gender balance is reversed, like the construction sector. However, designing programmes around the lived experience of women sets a more inclusive baseline, ensuring more opportunity for young people and more space for men to thrive, as well.

Many G20 countries, including South Africa, have made progress on closing the gender employment and earnings gap. This has taken concerted and coordinated effort, but as this report shows, there is still far to go. While some governments are beating a retreat from equity-based analysis and interventions, South Africa just cannot afford to. Many of the barriers that stop women from getting and keeping jobs are the same ones that all young workseekers face: lack of traditional experience, biases, low pay and low incentives. Our experience and data hold lessons for how to break these barriers and unleash more of women’s economic potential for their own, and society’s, benefit. We know which levers we need to pull, and now is the time to pull them.

One area in which South Africa has made notable gains is women’s participation in political and corporate leadership. More than ever, women who have themselves faced the barriers are in positions to bring their experience to bear. At the same time, there exists unprecedented alignment among a coalition of government, civil society and private sector actors on a national plan to turn the tide on youth unemployment: Vision 2030. The convergence of data, experience and coordinated action has the potential to bring about systemic change that benefits not just women, but all of us.

QLFS data from 2025’s second quarter reflect an interplay of marginal gains and persistent structural challenges in South Africa’s labour market, pushing the official unemployment rate to 33.2%. This amounts to a staggering 16.8 million people within the labour market without work. These alarming numbers do not, however, reflect another, more positive aspect: that the increase in unemployment has been driven by a decline in discouraged work-seekers and not necessarily lower employment levels. More of the working age population are engaging in active work-seeking: a potential reflection of hope and, perhaps, confidence in the economy. Zooming in on the 18 – 35-year old figures, the expanded youth unemployment rate moved downwards to 55.7%, whilst those not in employment, education or training (NEETs) reduced to just over 9 million. Whilst these are small wins, they are also reflective of a “new normal” of post-pandemic youth unemployment.

Gender inequality continues to shape labour market outcomes with ongoing disparities between men and women. Women’s unemployment stands at 35.9%, which is 4.9 percentage points higher than unemployment figures for men, and compared to a year ago, there are 68,000 fewer young women employed. The gender gap persists regardless of education levels, and is also reflected in the labour force participation gap, which was measured at 10.7%. Although women’s labour force participation has improved over the past decade (dropping from 12.9% in 2015), systemic factors, such as unpaid care responsibilities that women disproportionately shoulder, continue to impact what jobs can be taken up. The Q2 data indicates that nearly a third of all employed women work in Community and Social services, and occupations are often concentrated to lower- and semi-skilled roles.

Sectoral shifts are uneven: the formal sector added 34,000 jobs, reinforcing its dominance at 68.2% of total employment, while the informal sector contracted by 19,000. Geographic and demographic disparities also remain stark. Six provinces saw rising unemployment, with the Northern Cape jumping from 29.5% to 32.7%. The North West recorded the highest expanded unemployment rate at 54.7%, followed by Mpumalanga at 48.4%, with both provinces showing over 14 percentage points difference between official and expanded rates. Gauteng and the Eastern Cape led in employment gains, while the Western Cape and KwaZulu-Natal posted the largest losses. Over the past decade, the Western Cape has consistently maintained unemployment rates below the national average, while the Eastern Cape has remained above it.

Harambee in the News

30 Jan 2026

Harambee in the News: January

A snapshot of where Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator was featured in the media this month, reflecting ongoing conversations around youth employment, inclusive hiring, and the partnerships helping to connect young people to meaningful work opportunities across South Africa.

Harambee in the News

18 Feb 2025

Harambee in the News

15 Jan 2025