Building the Youth Economy in SA:

Services, Skills, and the AI Transition

18 February 2026

BREAKING BARRIERS

Quarterly Report

February 2026

Young South Africans earned their praise in the President’s State of the Nation Address with a record 88% matric pass rate in 2025. And although experts remain concerned about the distribution of these gains across subjects, the growing share of Bachelor’s passes, especially from no‑fee schools, signals that both performance and equity continue trending upward.

But a matric certificate does not guarantee a livelihood.

Most jobs require it; yet most matriculants enter a labour market still too small to absorb them. For those without matric, the barrier is even higher. Only 5% of online job postings accept non‑matric applicants, and Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) data shows NEET rates rise sharply with lower education: 32% among tertiary graduates, 50% among matric holders, and 81% among youth without matric. Without structured work‑readiness and work‑experience pathways, the transition into earning remains steep.

Young people are entering an economy in flux. Technology, demographics, geopolitics and the climate transition are reshaping work. South Africa is not alone in facing a slowdown in entry‑level hiring. Data from SA Youth and our partners shows a more nuanced picture: strong pockets of opportunity, and a clear mandate to act now to convert them into inclusive growth. But in a labour market that still places a premium on education, skills — not qualifications alone — are becoming the currency of mobility, and the shelf‑life of those skills is shrinking.

The President’s 2026 State of the Nation (SONA) address set out the case for South Africa’s economic potential. The progress of Operation Vulindlela in increasing the resilience, performance and dynamism of our key infrastructure has resulted in clear gains in electricity supply and energy reform, port and rail performance, and network coverage. These changes have strengthened economic recovery and improved investor confidence. Now, we need to ensure we build on this foundation and meet the headwinds of global change with a plan to reshape an economy that works for youth. The president described the shape of this new economy: one where inclusive, labour-intensive growth is powered by a “skills revolution” — the deliberate transformation and expansion of our systems for skills development.

South Africa’s emerging national plan for youth unemployment, Vision 2030, harnesses this momentum and optimism, laying out a pathway to increase youth employment by 1.8 million via inclusive hiring, unlocking opportunity in sunrise sectors, enabling self-employment, and sustaining public employment. These levers are underpinned by pathway management and demand-led skilling and provide the frame for the analysis that follows. Previously, we have spotlighted the critical need to expand and de-risk pathways to self-employment, calling attention to the many intermediary partners who offer support. We have also highlighted the importance of public employment programmes (PEPs), which provide vital on-ramps into the labour market, nurturing purpose and confidence, and providing much-needed services. The National Youth Service (NYS), Social Employment Fund (SEF) and YearBeyond programme continue to deliver on this strategy. The fourth phase of NYS, spearheaded by the NYDA, increased the number of opportunities to approximately 36,000, of which 67% were secured by women, bringing the NYS-reported cumulative opportunities across all four phases to more than 126,000. Place-based solutions such as the work of the Seriti Institute restore communities while building pathways. Alongside these programmes, self‑employment and micro‑enterprise remain essential to South Africa’s jobs strategy — providing income, autonomy, and resilience where formal jobs are scarce. Platform‑enabled work, township entrepreneurs, and service‑sector micro-businesses must be positioned as a core pillar, not an adjunct.

In this report, we focus on how we can disrupt skilling and strengthen access to, and retention within, the formal economy, which provides the bulk of employment in South Africa. Partners such as the Youth Employment Service (YES) continue to reach significant milestones, creating more than 209,000 formal work experiences for youth, injecting R12 billion into the economy through salaries, and achieving strong retention (45% employed; 15% in entrepreneurship). The task now: to expand the number and quality of formal jobs, and ensure youth are ready to succeed in them.

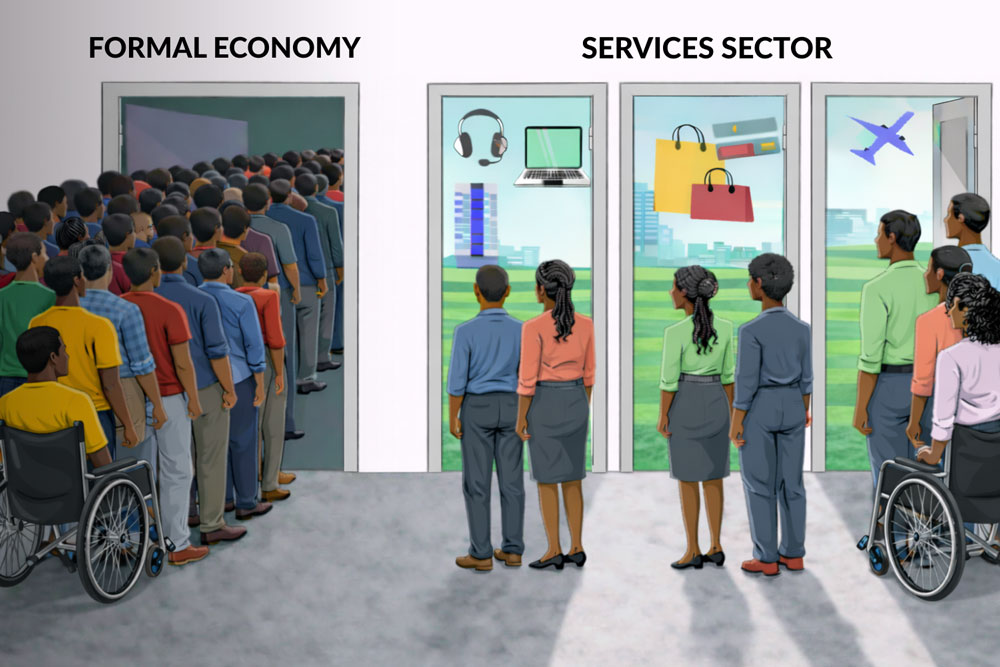

Insight 1. Formal jobs are scarce but transformative — and services offer the strongest pathways for youth.

Formal economy jobs are highly prized, hard-won and transformational for those who secure them. SA Youth data, describing over 240,000 young people’s transitions between opportunities, reflects that individuals who report a formal role also tend to report more opportunities overall. While PEPs and informal work widen entry, formal jobs sustain engagement. And the services industry — two‑thirds of GDP — offers the most youth‑accessible pathways into the labour market.

The services industry encompasses sectors like Retail, Tourism and Global Business Services (GBS). Retail plays the largest role in youth employment: Harambee’s income survey data indicates that close to 20% of the 4,508 working survey participants take up opportunities in Retail — a far higher proportion than other sectors and consistent with long-term trends. The sector offers reliable earnings over time, positioning it as a source of solid employment. We should build on this insight in the design of an industrial policy that drives inclusive, service-led growth.

Other services sectors are smaller but growing faster. Tourism offers significant opportunities: in 2025, South Africa welcomed a record 10.5 million plus visitors – a 17.6% increase in arrivals compared to 2024, which demonstrates accelerating momentum towards the Tourism Growth Partnership Plan target of 15 million visitors per year. Under this initiative, it is anticipated that up to 750,000 more direct and indirect jobs could be created by coordinating employment efforts with wider policy moves such as expanded electronic visa access, expanded air connectivity, visitor safety measures and infrastructure investment. Systemic unlocks, such as the recent launch of Electronic Travel Authorisation (ETA) to streamline the processing of short-term visas, are helping to position South Africa as a prime tourist destination. Over the next 12 months, the ETA will be rolled out to all countries requiring a visa, enabling tourist applications to be processed digitally within 24 hours. This coordination should be extended to include operators and providers of tourism-related products and services: transport, logistics, accommodation, restaurant, destinations, entertainment, and so forth. Sector work readiness programmes should be practical and designed to suit young people’s needs and sector nuances. Our own work-readiness experiments within tourism highlight the importance of SA geography knowledge (important to curate itineraries for clients), whereas in retail and hospitality, punctuality and strong customer experience skills are critical.

Another high-growth sector, GBS, has demonstrated the ability to create pathways into decent jobs, with 179,362 jobs created since 2010. This sector is particularly inclusive of people with disability and of women, who represent over 65% of new hires. Long-term labour market retention remains strong: a tracer survey of 753 individuals who were placed in the GBS sector between 2023 and 2025 reflected that 84% respondents are currently in formal employment. GBS employers—especially larger ones—tend to go beyond what is required legally, exceeding minimum wage requirements, investing in training and offering permanent employment contracts. These employers have shown employee safety and wellbeing to be a priority, with benefits specifically designed to contribute to work-life balance, such as the provision of transport solutions or stipends, and additional security measures. GBS employers are also pioneers in championing accessibility and disability inclusion, with industry body BPESA actively working to equip employers further in this space through Disability Inclusion resources.

GBS is also in the vanguard of sectors being rapidly reshaped by digitalisation and AI, with job types shifting toward more technology-driven and AI-enabled services. These shifts create disruption but also openings for those with different types of skills and profiles — so we must approach this not as an excuse for backsliding, but an opportunity for even greater inclusion. Looking ahead, the sector can future-proof itself by building training partnerships with higher education institutions, and pooling resources to build up new ‘foundational’ skills like AI and digital literacy, while ensuring general readiness for the world of work. Industrial and sector policies should be complemented by employer incentives that reward training and inclusive hiring — similar to incentives proven effective in GBS. But even as services create the strongest pathways for youth today, these very pathways are being re‑shaped by digitalisation and AI — disrupting tasks, roles and required capabilities.

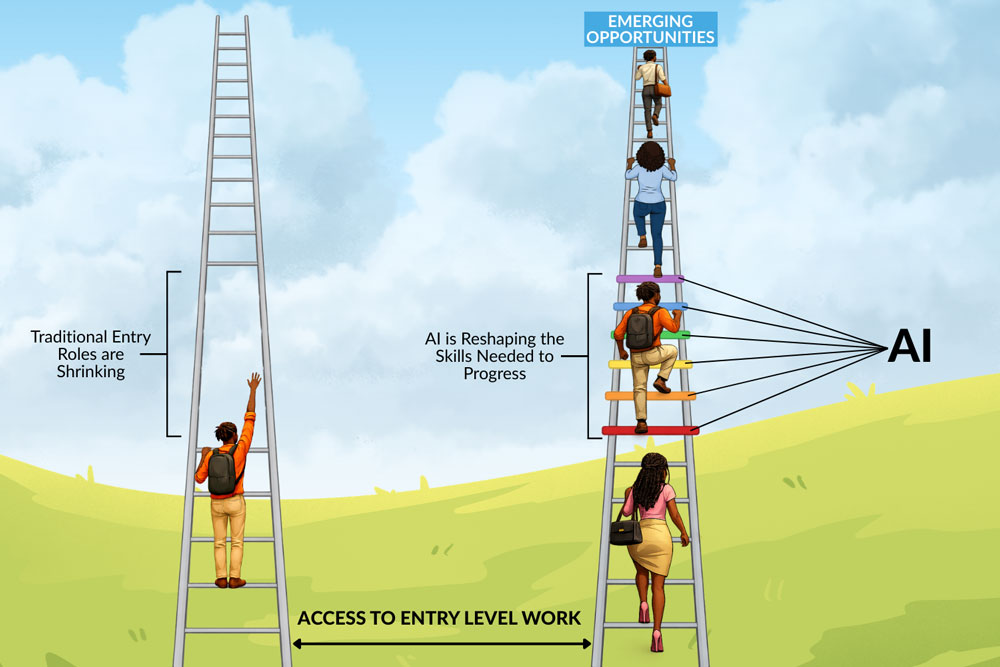

Insight 2. AI is reshaping entry-level work rather than eliminating it. We need to rapidly adapt to ensure economic inclusion.

South Africa’s AI market grew 31% year-on-year between 2023 and 2024. This does not translate automatically into job erosion, however: recent research by Harambee and Bridgespan indicates that, across markets, AI is reshaping jobs rather than eliminating them. Hybrid and higher-value roles are emerging that rely on human judgement, emotional intelligence, and contextual understanding.

Human oversight of AI agents remains essential to manage outputs, ensure accuracy, and maintain authentic customer engagement, especially with complex customer experience work for regulated sectors.

South Africa’s value proposition within the global labour market sets us apart from low-cost competitor countries, whose only strategy is to scale automation. We have an acknowledged cultural and linguistic advantage when it comes to complex customer experience work — the kind that requires high empathy, intuition and English proficiency. By investing in the excellent delivery of these human-centred customer interactions, South Africa can differentiate itself and sustain the competitiveness that fuels job growth and quality. Doing this requires the purposeful and strategic adoption of automation to ensure it augments human skill rather than replacing it.

The greatest risk is a mismatch between the pace of task change and the pace of skills development and transition — and this risk is unevenly distributed, especially within the services sector: over 40% of current tasks in Africa’s Business Process Outsourcing (BPO) and IT Enabled Services sectors are susceptible to automation. Those most exposed to this risk are those doing repetitive tasks in roles like customer service, data entry and administrative support: all disproportionately junior, entry-level positions in which women and youth are highly concentrated.

Two scenarios could play out: a scenario where AI augments, and one where AI replaces. In the first, AI supports humans to deliver better customer service and experience, by handling routine tasks and optimising decision-making. This scenario enhances South Africa’s position in complex, empathy-led customer experience and supports clear pathways from entry-level roles into higher-value, hybrid work. But this scenario requires intentional, coordinated action: targeted investments in AI and data policy frameworks, digital infrastructure, inclusive reskilling and AI access, and public-private collaboration. Without this, the second scenario is more likely: AI is used to cut costs by taking humans out of the equation altogether. This can erode South Africa’s competitive edge as a global player in the services sector, shifting demand elsewhere. In this scenario, entry-level roles are more likely to be automated away, and higher-value roles become more specialised and less accessible to women and youth.

To achieve the first scenario, we must influence AI adoption so that it facilitates new on-ramps and be intentional about who gets access to them. This means redesigning roles for human-AI collaboration and building much more adaptive, demand-led skilling systems. Young people will need to acquire new types of ‘cool’ skills, such as AI literacy and data competencies, and learn how to combine these with their ‘warm’ human skills that South Africa is known for: empathy, judgement, and contextual understanding. In the SA Youth contact centre, AI is used as a human‑centred support capability serving the 5 million+ youth in the SA Youth network – helping agents deliver safer, more empathetic and consistent service at scale through real‑time assistance, safety monitoring and intelligent routing. This values‑led approach strengthens youth protection and service quality while building future‑of‑work skills for young people, ensuring AI increases impact without replacing the human conversation at the core of our work.

In Tourism, AI can automate tasks like booking and customer support, but also fuels demand for the hyper-personalised support that generative AI provides, like curated itineraries and recommendations. This opens the door to new opportunities, including for the self-employed, gig- or small-enterprise workers (such as vendors of food, transport, tours, crafts, and personal services), who can connect to global interest and demand via platforms. New entrepreneurial roles are emerging, such as local content creators, experience hosts, virtual tour curators, AI-assisted itinerary builders and community-based data collectors. As with GBS, frontline roles in Tourism will increasingly need to blend human warmth with digital fluency. However, many jobs in the sector resist being completely replaced — like flight attendants, security staff, maintenance, culinary and cruise operators. This paints an optimistic future for tourism in South Africa, with widespread AI integration anticipated to support up to 1.28 million jobs in the tourism sector by 2030— 75,000 more direct jobs than if no AI investment took place.

Across the economy, AI’s impact is inevitable. Its inclusivity is not. Steering AI adoption toward job creation and away from displacement is the central economic challenge of the next decade.

Insight 3. To ensure our youth are future‑fit, South Africa needs a wholesale “skills revolution” — one that is demand‑led, modular, outcomes‑driven, and co‑financed by employers.

In the new economy, the how of skill-building is as important as the what: we need a responsive model that builds ‘stackable’ skills. And the skills funding needs to be responsive and nimble, with employer “skin in the game.”

AI is one megatrend shaping a new economy. Climate change is another. Like AI, the energy transition will both destroy and create jobs, but is anticipated to drive net job creation globally, potentially creating nearly 375 million new jobs in the next decade across Energy, Construction, Manufacturing and Agriculture sectors. But these new jobs will not emerge in the same places as old ones, and many of them will require entirely new skills, new ways of skilling, and new modalities of funding. Together, these megatrends have huge implications for the future of work. By using the word “revolution” in his State of the Nation Address, the President is signalling the scale of change required, not only in the skills themselves, but in the entire model that delivers them.

Our experience suggests that skilling systems need to transform in three key ways:

First, they need to become demand-responsive and adaptive. At a policy level, this requires SETAs and skilling institutions to evolve their curricula and standards in line with shifting industry needs. It also means scaling approaches like that of Collective X, which is addressing the digital skills shortage in South Africa jointly with private and public stakeholders. Instead of skilling for routine, predictable tasks, employers and training institutions need to prepare workers and job-seekers for adaptive, tech-enabled work, blending digital literacy, technical skills and problem-solving. FirstSource, a leading global provider of business management services, is using AI to fast-track how employees learn, grow, and succeed — delivering personalised coaching at scale, enhancing career pathways and increasing speed-to-competency. Skilling providers should make AI literacy a core component across all training programmes from the outset, focusing on foundational skills, as well as specialised ones whose value AI may erode. Programmes should be agile and learner-centred, avoiding rigid curricula and enabling a constant dialogue with employers and learners. Work-integrated learning (WIL) programme models such as those pioneered by Vodacom and Harambee, and scaled by Collective X, have a track record of low attrition and high post-programme absorption.

Second, training systems need to anticipate flux by building modular, ‘stackable’ skills. Rather than just training for a particular workflow or moving cohorts toward a single credential that may quickly become obsolete, ‘stackable skills’ move the focus from a narrow set of technical job-specific competencies to a mix of capabilities that can be combined in multiple ways and are transferable across roles. This creates a win-win: employees enhance their employability and employers increase the flexibility of their workforce. The model is being advanced by organisations like WeThinkCode, who train for stackable, industry-relevant skills through a two-year, NQF5-accredited programme that integrates soft skills and cultivates sector partnerships to sustain relevance. More than 1,867 youth have moved through a WeThinkCode programme with a 81% placement rate. This approach shifts the focus from a single qualification to a lifelong sequence of micro‑credentials, portable signals and verified capabilities — giving young people multiple ‘on‑ramps’ into work and multiple ways to advance.

Employers cannot rely only on third-party providers to make this new stackable skilling model work. They must shift from being passive consumers of talent to active co-creators of it. Pooling resources to co-design curricula for sector-specific skills will ensure a talent pipeline that is responsive to demand. AI can provide the means as well as the incentive. For example, Concentrix uses AI tools such as Genie and Dot to augment internal operations, streamline communications, and support knowledge discovery across the enterprise [Everest Group, 2025]. Tools like these offer the ability to tailor support to meet young people where they are, setting them up for quick success, which is particularly important in entry-level roles. Tailored support may include language translations, text-to-audio/voice-to-text transcription services or personalised e-learning modules. Inclusive hiring practices that value competencies (e.g. behaviour and problem-solving) beyond traditional qualifications further widen the talent net available. To enable this, accreditation models should be expanded beyond programme completion to include Recognition of Prior Learning, portable certification and micro-credentialing on market-relevant competencies. This includes innovations like SA Youth’s inclusive CV, which provides additional signals to the labour market by including results from the rigorously tested Learning Potential and Behavioural screeners that are proven ways to increase access and improve recruitment and employment outcomes.

The third change is in how we finance skills acquisition.

Our funding mechanisms need to be overhauled so that they are outcomes-led — i.e. payment tied to the delivery of outcomes rather than inputs and activities — and ensure that employers have “skin in the game.” Both Jobs Boost and The Jobs Fund are designed this way, and have led to innovation, much closer engagement with employers, and strong employment outcomes for learners. Policymakers can create the enabling environment by optimising skill development levies to include all types of skilling initiatives (non-accredited, micro-credentialing, work-integrated learning), to unlock the full potential of workforce funding available. With incentives such as tax credits (as seen in the GBS sector) and investment subsidies, employers are equipped to invest in the skills, job creation and inclusive employment required for the new economy.

The skills revolution hinges on effective pathway management, such as that offered by the SA Youth platform, in order to support young people — smoothing the churn in and out of a volatile labour market, optimising transitions, and ensuring they stay in the economy and continue to earn.

Conclusion

South Africa can choose growth that has room for more of its youth. Vision 2030 sets the ambition: an economy powered by labour‑intensive services, expanded pathways into enterprise, and a transformed skills ecosystem that prepares young people for a world where skills — not qualifications — determine mobility.

The charge now is clear: grow and upgrade formal jobs in services, leveraging them as an entry-point for young people; steer AI adoption to augment human work, not replace it; and catalyse the “skills revolution” for young people to take up these opportunities. By embracing the President’s call to action, we can create a demand‑led, modular, outcomes‑funded skills system with employers as co‑investors.

If we align incentives, infrastructure and skilling to the new economy — not the one we are leaving behind — the class of 2025 will not wait at the margins, and an additional 1.8 million youth livelihoods by 2030 becomes achievable. Young people will be the competitive advantage that powers South Africa’s future.

QLFS Update

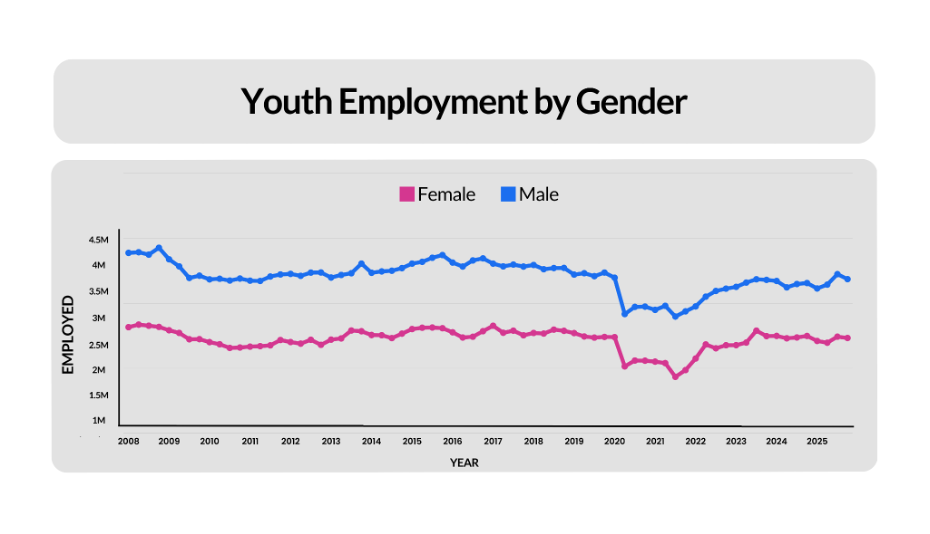

The recently released Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS) showed a welcome decrease in the official unemployment rate by half a percentage point to 31.4% in Q4 2025. Formal employment was a significant driver, with an increase of 320,000 jobs, mostly in Services (46,000), Construction (35,000) and Finance (32,000). This further reinforces these pathways for youth to work.

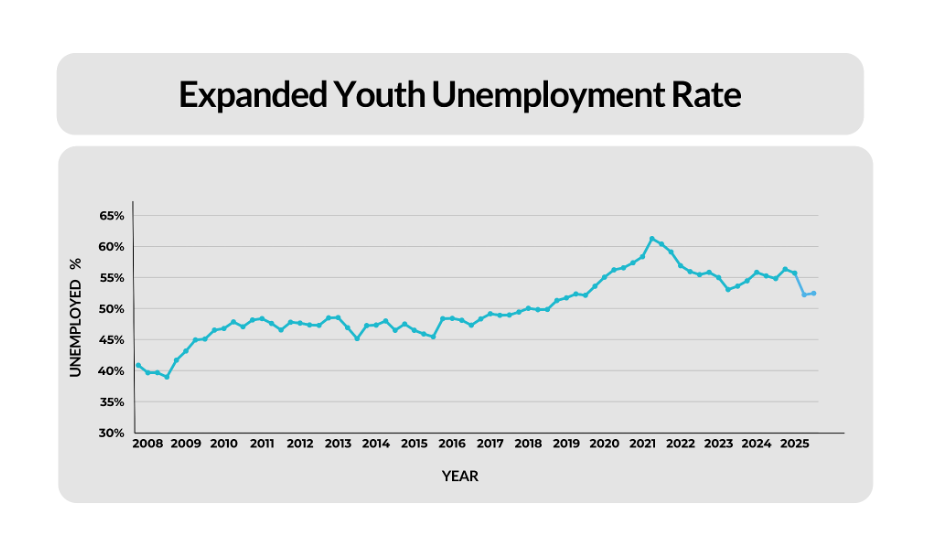

Looking at the data from a youth lens, young people continue to have the highest unemployment rates. For youth aged 18-35 years, the broad unemployment rate remained relatively constant at 52.43%, with the number of NEET youth remaining stable at 8.8 million. Despite this, the number of employed young people declined by almost 100,000 jobs. Youth employment declined without a mirroring increase in unemployment due to the fact that a number of young people (147,000) left the labour force completely.

New categories, such as Potential Labour Force, provide line of sight to nuances in unemployment data: one of the main reasons Stats SA announced in the Q3 2025 that it had made changes to how it tracks labour market status and informal employment. The introduction of two new labour market metrics – available and unavailable jobseekers – allows us to better identify the reasons people might be unemployed. For example, available jobseekers could work but are not looking for it because they are waiting for seasonal work, health, disability or family responsibility reasons, or lack money for transport – a critical barrier to labour market entry. These jobseekers are different to discouraged work-seekers who have stopped looking for work altogether because they were unable to find any work after some time searching. Unavailable jobseekers are those who are looking for work but are not available to do it just yet, such as a student who needs to finish studying. The Potential Labour Force is made up of these two groups, and over the last quarter saw an increase of 82,000 people across the full labour market, with discouraged job-seekers dominating the share, accounting for 80.5% of the total 4.6 million. By better understanding groups like these, labour market interventions can be adjusted to respond better to the challenges facing youth not engaged in earning opportunities.

Also updated in Stats SA’s new metrics is the informal employment definition, which removed the size of the business as a criterion for determining formality, and instead uses indicators like the business’s registration status, VAT status and employee benefits (e.g., pays UIF, sick leave) – a more accurate measurement of structured employment. Agriculture is also now considered as an industry, and is no longer split out from formal or informal work. The changes in the informal employment definitions mean that informal employment statistics from Q3 and Q4 2025 QLFS cannot be directly compared to previous surveys. However, the changes simplify the informal economy, making it easier to understand and track going forward. Given the importance of informal work in providing jobs for young people when the formal economy is unable to, this clearer definition is welcomed.

NEED MORE INFORMATION?

WANT AN OFFLINE VERSION?

Stay Connected

Stay Connected