SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

12 November 2025

South Africa’s formal sector is shedding jobs at a worrying rate. This is according to both the latest Quarterly Employment Survey (QES) and the Quarterly Labour Force Survey (QLFS), which support the finding that there are 200,000 fewer individuals in formal employment than there were in the first quarter of 2023. Even though wage employment remains an economic priority for job creation, young people cannot wait for opportunities to just materialise. We need to harness other forms of employment as vehicles for young people to earn. Self-employment, often seen as a stop-gap, could become an effective vehicle for young people’s economic empowerment if supported well.

Self-employment is already a crucial part of South Africa’s economy. Harambee defines this as the selling of products or services as a primary activity without relying on wage employment. It encompasses a few different groupings–young people who sell vetkoeks, airtime, cell phone chargers, clothes, sweets, cigarettes and more, from their homes, markets, street corners, and taxi ranks; youth that braid hair, do nails, and look after neighbours’ children; those that fix windscreens on the side of the road, guard cars, collect plastic and cardboard for recycling, or wait for days outside the hardware shop for one day of piecework. It also includes youth who are fashion designers, provide backyard rentals and digital freelancing. What we’ve learnt from the SA Youth platform is that those who do these activities on their own seldom earn more than R1,000 per month. Another group of self-employed youth earn closer to R3,000 per month, and these are generally people who work through an intermediary, for instance by undertaking driving services or handyman skills for platform providers. Still, neither of these groups, on average, earns close to minimum wage.

A third group are those who have found commercially viable business models–e.g. solar installation, logistics businesses, etc.–and are earning above minimum wage. These individuals are able to access the support needed to make this work, whether it be resources, financing, equipment, mentorship or access to markets. This group provides the business case for self-employment as an economic growth area.

The definition of youth who are self-employed is distinct from youth establishing small and medium enterprises (SMEs) with multiple employees and those engaged in wage work in unregistered (informal) enterprises. We measure success in self-employment by earnings: individuals generating sufficient and reliable income. Finding ways to sustain higher and longer earnings must, therefore, be an area of focus within the labour market, given flatlined formal economy growth. Youth self-employment—whether through community-based activities or participation in the platform, or gig economy—presents an alternative to job-seeking against declining odds and is a critical part of the future of work.

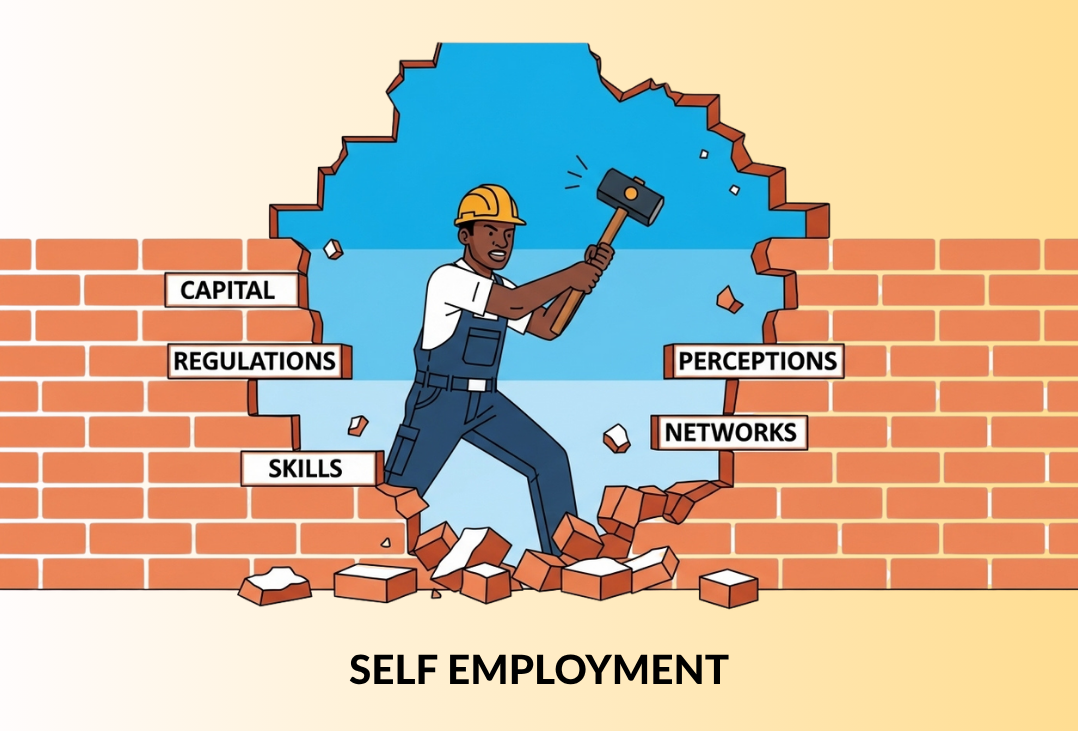

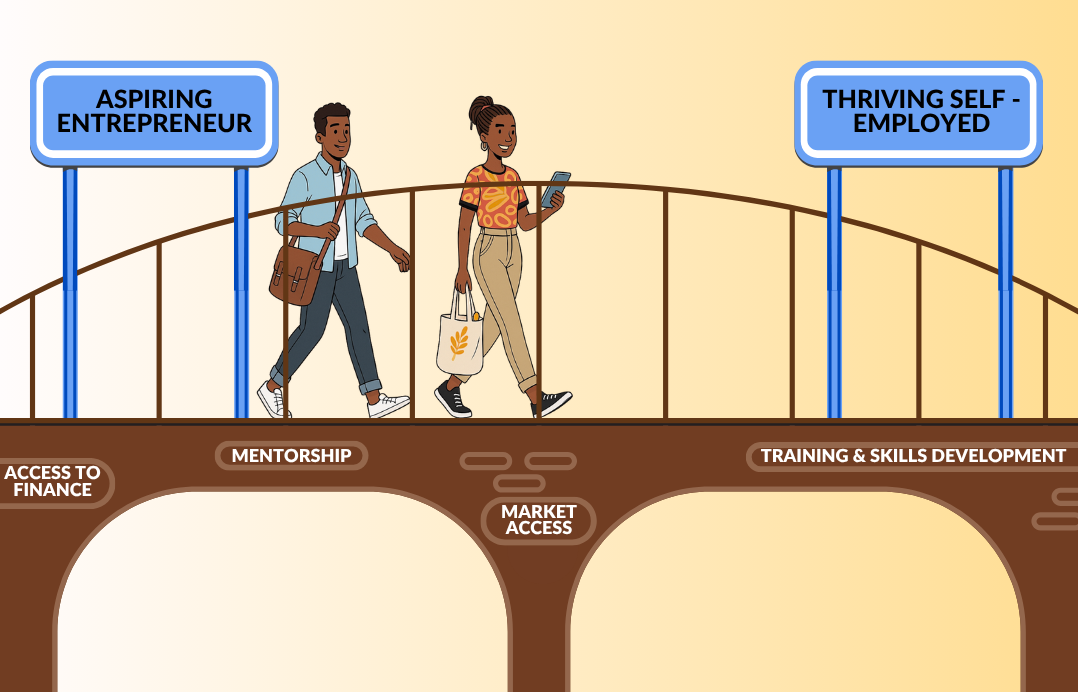

Though there exists support to start and grow a new business, few institutions support youth aspiring to small-scale self-employment. Self-employment receives far less attention than broader start-up, enterprise and supplier development efforts, with their well-developed and funded ecosystems. These ecosystems are often not at the right channel for the greatest impact, nor are they well coordinated. We need strengthened policy coordination and a schooling system which is not purely geared towards the expectation of formal sector jobs.

That is why this Global Entrepreneurship Month, we are calling attention to the promise and perils of self-employment. On SA Youth, 24% of the actively engaged youth who are earning, reported a self-employment opportunity. Young people are ready to work, and South Africa needs to enable an ecosystem that makes self-employment a viable and desirable livelihood path. This is so that, by 2030, more youth can earn consistent and reliable incomes without relying on formal jobs alone.

South Africa is an anomaly. Despite having one of the highest unemployment rates globally, the country has an informal sector that is vastly undersized compared to many other upper middle-income countries. The informal sector contributes only 6% to GDP in South Africa, compared to 45% in India and 20% in Brazil. Under the new definition of the informal sector, about 23% of those working are in the informal economy, with the rest in the formal economy (QLFS, Q3 2025). While some argue that the informal economy is severely under-counted, more accurately calculating the size of the sector overall matters less than the ability of individuals to translate their informal work into durable and decent earnings. Historically, support for the sector has focused on growth-oriented micro enterprises, but these make up only 27% of the informal market, whilst ‘survivalists’ contribute a 73% share (Burger & Makaluza, 2018). The latter struggle the most, facing a lack of support, poor sustainability, and stigma.

South Africa’s bias towards formality bleeds into every facet of society: the school system, our regulatory frameworks, our culture and language, and historically, our entrepreneurship scaffolding. Young people avoid self-employment because they see it as an ignoble last resort, or simply because they are unable to conceptualise opportunities that might work for them. A mindset shift is needed to attract disengaged youth into self-employment, but dedicated support for this is missing in the ecosystem.

This kind of support can take several forms. Exposing young people to relatable, successful self-employed role models enables them to see the steps involved in making money for themselves and to believe they can do it. Peer validation and celebration of the hustling qualities of resilience, creativity and resourcefulness help young people construct positive hustler identities. They are less likely to see self-employment as a dead-end if they can identify the skills it builds and show how these translate to other types of employment. The recently launched SA Youth downloadable CV is designed to help make informal and unpaid work visible, providing a way for young people to capture the value of their entrepreneurship skills and signal them to the market. By asking good questions about all the work young people do, the CV enables us to better count and value this work, further reducing the stigma around self-employment. It also allows organisations that run entrepreneurship programmes to better identify suitable candidates, based on their self-employment activities. Early results indicate that almost a quarter of the 273,439 young people who have used the CV have gone on to update their details—an important stimulus to labour market engagement.

Nowhere is the formality bias more clear than in the financing of self-employment. The conventional business financing ecosystem is not structured for self-employment and is therefore out of reach for self-employed youth. Providers of small business loans, impact investors and even venture capital all target their investments towards high growth-potential start-ups or SMEs with an established track record. Most established banks are reluctant to serve self-employed youth due to their risk-averse lending practices, even though they may serve a young person as an individual. There are exceptions, however, with some banks, like Capitec, making an encouraging drive to expand services into the informal economy.

The other source of finance for small enterprises is government-backed financial institutions, subsidies and grants. This often requires business registration to unlock funding, which is an unrealistic requirement for many young self-employed people. There are, however, several ways the government can shift the way it provides finance. One is the reimagining of public processes to reduce barriers to registration—as seen with the Bana Pele Mass Registration Drive by the Department of Basic Education. Another is by channeling funding through intermediaries. The Gauteng Enterprise Propeller is an example of this, providing funding to intermediaries for rural and township enterprise development. In another example, the Jobs Fund offers challenge funding with specific enterprise development and informal economy windows. Alternative finance providers can also fill the gap, with lending models that accommodate the riskier nature of early-stage self-employment activities. For instance, uMaStandi provides 80% of upfront capital support for township property entrepreneurs to develop backyard rental offerings. Spoon Money supports women-run informal traders to set up savings groups to access small business loans, and the Small Enterprise Foundation provides micro-credit to female entrepreneurs in savings groups, already serving over 174,635 individuals.

Starting a micro-business is one thing; sustaining it is another. Among those young people who take their first steps into self-employment, many will not be able to maintain it thanks to narrow margins, competition, personal shocks, and a lack of accessible, fit-for-purpose support. Addressing this requires harmonised work between organisations engaged in the ecosystem: first, to get young people to pursue self-employment pathways; then to ensure the relevant support, such as financing, is available to them; and finally, to build their resilience. Funders can play a key coordination role by funding implementing partners and convening entrepreneurial communities of practice, as seen in the work of the Allan Gray Orbis Foundation. Over the past 20 years, the Foundation has supported 572 entrepreneurial ventures, of which 59% became viable businesses collectively employing 2,976 individuals and generating R2.1 billion in revenue. By creating greater coherence in how best to support self-employment—including alignment on metrics and shared understanding of what works—funders can play a key role in mobilising the ecosystem.

At the lowest end of the self-employment spectrum, we see a multi-faceted interaction between receipt of the Social Relief of Distress (SRD) and Child Support Grants, and self-employment activity. Research on the effect of such cash transfers on employment outcomes, including self-employment, all show positive effects (Bhorat, Kholer ; Orkin et al ; Khowa et al). What’s more, there is no evidence that grant dependency negatively affects people’s participation in the economy. Rather, for the self-employed, these grants seem to act as a micro-investment in stock and a buffer against financial strain. These positive impacts are reduced, however, by the low income threshold for receiving the SRD and the electronic means test via the banking system, both of which incentivise people to keep bank balances small. This crowds out the kinds of financial transaction and investment innovations, like mobile banking and savings, which have fueled growth and innovation in other developing informal economies. To increase the positive impact of the SRD on self-employment, some researchers suggest increasing the eligibility threshold substantially, and to also increase the time between conducting the periodic means tests.

We define ‘scaffolding’ as support that helps youth overcome the barriers to income generation through self-employment. Practical inputs include training, mentorship, start-up kits, access to equipment, market access, working capital, data subsidies, peer groups and other targeted forms of support. Scaffolding takes several forms:

Each of these models serves a specific community within the self-employment landscape. All work towards creating decent and enduring earnings for young people.

Another important source of scaffolding provision is PEPs. These combine temporary wage-earning work opportunities with skills training. Furthermore, research suggests that the wages from these programmes do not just ‘disappear’, but circulate in the local economy and contribute to other forms of earning. Increasingly, the administrators of these programmes are looking at ways to help beneficiaries enter self-employment once their temporary work ends. One approach is to increase coordination between large-scale PEPs such as the National Youth Service, Expanded Public Works Programme, Social Employment Fund, and the Basic Education Employment Initiative. Another is to tighten coordination and alignment with an existing sectoral strategy, for instance, the regulatory reforms, training and micro-finance support featured in the 2030 Strategy for Early Childhood Development. This ensures that young people walk away from PEPs equipped to work in a sector where they’re set up for success.

Finally, educational organisations form an important pillar of South Africa’s self-employment infrastructure by offering learning that is focused on starting and growing a business. Schools can play a key role in exposing young people to alternative career pathways and foundational entrepreneurial skillsets (thereby legitimising these activities in young people’s eyes). However, we need targeted entrepreneurship education to help young people translate a business idea into a self-employment enterprise. This can be delivered equally well by higher education institutions or Edtech online programmes, provided the programme drives towards clear outcomes.

Supply-side interventions like those described above encourage young people to take up – and stick with – self-employment, but for the economy to grow and meet its potential, this needs to be matched with demand for such activities. It is easy to look at the small-scale self-employed and see a chaotic mass of unstructured activity but our data shows that there is a hidden order that is just as responsive to the intentional coordination found in large businesses.

Gig platforms demonstrate this. They both aggregate demand and provide a form of scaffolding that attracts young people and matches them to this demand. Benefits include improved safety, flexibility and a bridge to wage employment, as well as training, both formal and on-the-job, in transferable skills like sales techniques, customer engagement, and conflict resolution.

However, the Jobtech Alliance’s research on gig platforms across Africa highlights that the largest share of gig workers earn only small, supplementary amounts, estimated at $60 (R1,031) or less across six months. The prevalence of such ‘micro-earning’ means that platform work is not always translating into reliable, sufficient income. The problem isn’t always the pay: it’s the unpredictable volume of opportunities. Structural factors within the platforms can worsen this: many are designed to spread work (and therefore earnings) thinly across a large user base, some suffer from limited customer uptake or market penetration, or create a market imbalance by onboarding too many workers in low-demand categories. Over half of all gig workers remain in the micro-earner category. This is a problem because for many gig workers, this is not a side-hustle—i.e. supplementary income used to top up a salary—but their main source of income. People are relying on often meagre gig-work earnings to survive.

Ecosystem players can help by working to unlock latent demand in self-employment sectors such as last-mile delivery, hair and beauty, food production, street retail, design, property services, transport, and personal care. Platforms in these markets, which straddle the formal and informal economies, can offer pathways to more secure work, where a young person’s gigs form a stepping stone to something more formal in the same sector, or teach skills they can use to seek other work. However, we need to better understand the earnings distributions, stickiness and drop-off of such activities, so that we can convert more active gig workers to consistent earners.

Demand aggregation helps self-employed young people access earnings, but we also need to stimulate new demand. This can be done at multiple points in the value chain. Consumer demand, where customer expenditure generates business activity, is an important lever and significant shifts in the underlying infrastructure of consumer demand can open up new markets rapidly. In South Africa’s financial services sector, for example, recent innovations have greatly increased financial inclusion for the self-employed. Yoco’s standalone and low-cost card machines have enabled flexibility and accessibility amongst self-employed traders. Tyme Bank has pioneered an inclusive and affordable product offering, including SendMoney, which enables the low-cost, peer-to-peer transfer of funds via cellphones. Tyme Bank’s model keeps banking fees low by moving away from brick-and-mortar locations, reducing operational costs. By enabling more types of transactions between more people, these innovations oil the machinery of demand to unlock more of what’s already there.

Another lever for demand-creation is the third-party enterprise and supplier development (ESD) value chain. Large companies that specifically support SMME entrepreneurship through such channels are finding that this contributes to a flourishing informal sector, which can ultimately create additional consumers for their own products and services. Standard Bank research found that 28% of township businesses in their sample contributed to the local value chain by paying other businesses for services. This highlights the fragmentation and interdependence in localised ecosystems: some of the money directed to a township SMME may well end up in the hands of a smaller and less formal entrepreneur. Standard Bank’s ESD strategy seeks to support township SMMEs by enabling access to finance, business development and markets. Unilever is another organisation that has significantly increased its support for SMMEs, with local sourcing rising from 40% in 2019 to an expected 80% by 2025. At present, 95% of their products are produced locally and over R100 million has been contributed via the ESD Fund, promoting local economic development.

As in the formal economy, taking a sector-specific lens can help target self-employment support where the greatest potential exists. In South Africa, the services industry has particular promise for self-employment growth. South Africa’s economy is more service-heavy than those of many other middle-income countries: services generate two-thirds of GDP and employment. In similarly-sized economies, sectors such as manufacturing and agri-processing are usually an entry-point for entrepreneurs, but in South Africa, these sectors are highly concentrated, with many essential goods being mass-produced by a small group of firms. This creates high barriers to entry for entrepreneurs (Philip, 2025). By contrast, service industries such as tourism, hospitality, retail, and logistics are more accessible and inclusive (six out of seven service jobs are held by women). Crucially, these sectors have been growing continuously since 2008 and have been integral in supporting entrepreneurship, innovation and flexible production across the economy. For example, South Africa’s Tourism and Hospitality sector has grown from employing 600,000 people in 2008 (4.4% of the employed population), to employing 1.8 million people in 2024 (11% of the employed population). Likewise, Transport and Logistics has grown from employing a 5.6% share of the employed population in 2008, to employing 6.6% in 2025 (QLFS, Q2 2008 and Q2 2025).

As we think about stimulating demand to create new opportunities for entrepreneurship, we also need to take a medium to long-term view on how to shape this demand. This means prioritising self-employment in industrial policy, deploying mechanisms such as financial incentives and subsidies, with improved system coordination, to curate an ecosystem of entrepreneurship. It also means thinking beyond national borders, understanding how South Africa can plug into international value chains and leverage cross-border markets, as is already occurring in the Global Business Services (GBS) sector. Between 2010 and March 2025, the international GBS sector generated a cumulative export revenue of $2.783 billion and created 173,944 jobs most of which went to youth. Other priority sectors such as the digital economy, the green economy and tourism, are both poised for growth and lend themselves to entrepreneurial activity. With these, we can take a leaf out of the GBS book, incorporating their potential into industrial policy and developing incentives.

Growing the market for self-employment is critical for the future of work and crucial to meeting South Africa’s ambitious goals for reducing youth unemployment by 10%-20% by 2030. This means working together to tackle barriers on the supply and demand side so that self-employment is no longer seen as a last-resort, survivalist activity, but rather an aspirational and productive pathway in a national economy that’s set up to enable large-scale youth income generation. The future shape of such an economy may look different, but these measures can ensure it is bigger and better for all.

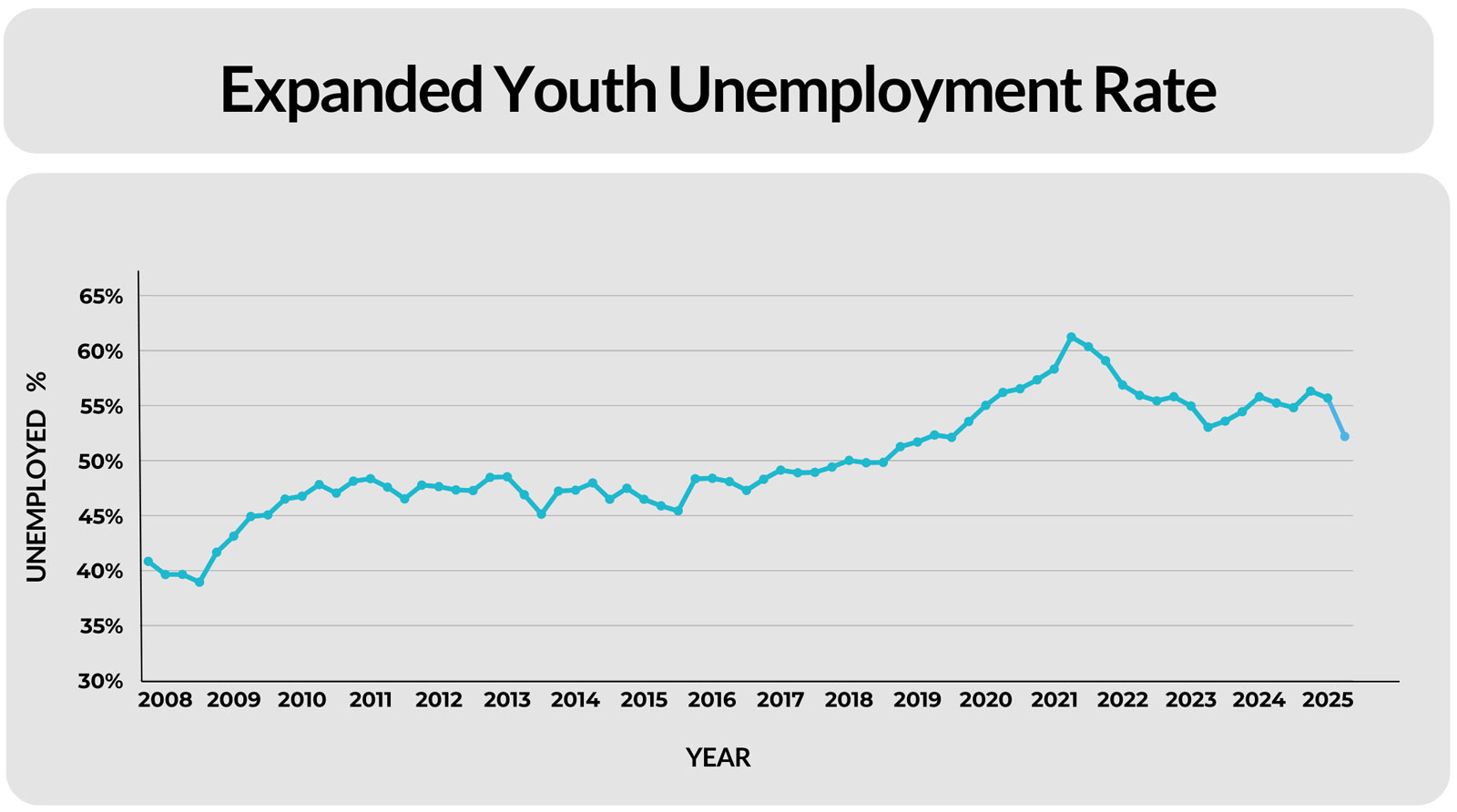

We are cautiously optimistic about the unprecedented rise in youth employment quarter on quarter.

Our Breaking Barriers report always coincides with the release of Stats SA’s Quarterly Labour Force Survey, and includes our high level commentary on its results. This quarter comes with a few changes to both the QLFS methodology and also the level of detail released; implying delays on some of our usual longitudinal comparisons. From a youth lens, here is what the QLFS release tells us:

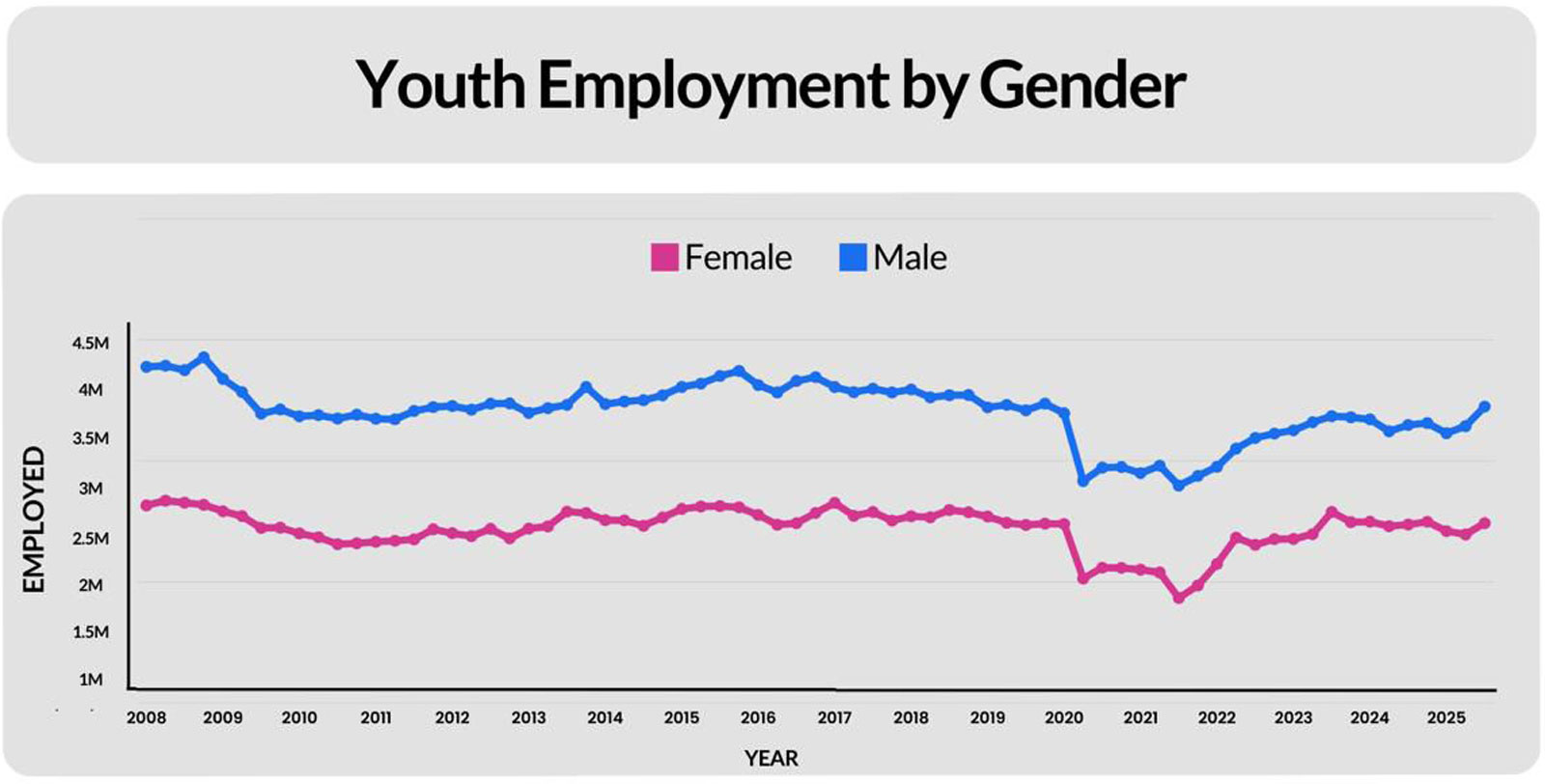

Employment for those under 35 increased by 265,000 – this is the biggest quarter on quarter youth increase since measurement began if we exclude the Covid-19 recovery period. This takes youth employment back to just under 6 million, and implies a 2.4 percentage point improvement in the youth unemployment rate quarter on quarter. As more detail is released we might gain more insight about the gender, sector or geographical gains. For example, with mass public employment programmes such as the Basic Education Employment Initiative in progress, it is possible that this is being reflected in the data to some extent. This improvement in the number of youth aged 15-34 years employed is also reflected in a reduction in the strict youth unemployment rate: from 46% in Q2 2025 to 43.7% in Q3 2025.

However, although the increase in the number of youth employed is welcome, the proportion of youth who are NEET (not in Employment, Education or Training) remains worrying. More than 40% of those under 35 are NEET, and in the past year, this figure has declined only marginally from 43.2% in Q3 2024 to 42.7% in Q3 2025. Whilst this past quarter shows significant progress for young people, more is required across the economy for earning opportunities to be realised.

For the whole economy, the latest QLFS figures for Q3 reflect a labour market in movement. Statistics reflect the official unemployment rate decreased by 1.3 percentage points from 33.2% in Q2 to 31.9% in Q3 2025. Sectors that contributed to this include Construction, Community and Social Services and Trade.

This past month, Stats SA introduced key changes to QLFS measurements, including new definitions for the informal sector and informal employment. Informal employment are individuals in precarious employment circumstances, who do not have access to social protection benefits such as pension or paid leave, regardless of whether it is in the informal or formal sector. The informal sector comprises economic activity by individuals in entities that are not registered. Given these new definitions, the informal sector-sized at approximately 4 million individuals-cannot be compared to previous quarters. As a new baseline informal participation rate, we can note that the employed population is now split 70% / 23% / 7% between Formal / Informal / Private Households.

Stats SA also introduced Labour Market Underutilisation to reflect the total number of people in the economy who are not being fully utilised-whether it be due to unemployment, underemployment, or potential labour supply currently outside of the labour force due to discouragement, household responsibilities, or other. These new metrics provide a more comprehensive picture of the complexity of the labour market in South Africa, and further reflect the unmet need for employment amongst the working age population.