SA Youth connects young people to work and employers to a pool of entry level talent.

Are you a work-seeker?

8 May 2025

How can nonprofits and nongovernmental organisations (NGOs) help far more people while keeping their own organisations at a sustainable size and cost? In 2014, The Bridgespan Group’s Jeffrey Bradach and Abe Grindle explored this question in “Transformative Scale: The Future of Growing What Works.” They examined pathways to deliver impact at a scale that truly meets significant social needs.

A decade later, we take another look at pathways for solving social problems at scale. To do so, we tapped into Bridgespan team members’ experience working with nonprofits and NGOs in the United States, Asia, and Africa to develop scalable strategies to address social problems. For this update, we examined the strategies of approximately 80 organisations and interviewed the leaders of 11 of these organisations on their journeys to scale their impact.

This article provides an updated guide to the pathways, or core strategy components, that nonprofits and NGOs use to deliver outsized impact on social problems while keeping their organisations’ size and growth manageable. We did not look specifically at how organizations expand their direct services—opening new sites, serving more clients—because this typically requires a corresponding increase in size and cost. However, direct service growth can have a powerful impact on social change, particularly as a source of organizations’ credibility and evidence base. Indeed, even as organizations pursue one or more of the pathways identified below, they may also continue or even expand their direct service work to create even more impact.

A Note on Methodology

Most of the 80 organizations in our dataset are funded by one of three funding collaboratives with which Bridgespan has worked—the Audacious Project, Blue Meridian Partners, and Co-Impact. We also examined the current strategies of other organizations featured in Bridgespan’s original 2014 article on transformative scale. Of course, this isn’t a fully representative sample. We recognize that the organizations studied for this research are disproportionately represented by these collaboratives and, inevitably, they reflect the interests of those funding sources.

Yet, the organizations represent a wide range of issue areas, working in the United States and globally. Additionally, almost all have received substantial funds from at least one funder to explicitly support their strategies to solve social problems at scale. This sample provides us a rare opportunity to look in detail at how scores of nonprofits and NGOs are working to solve social problems at scale.

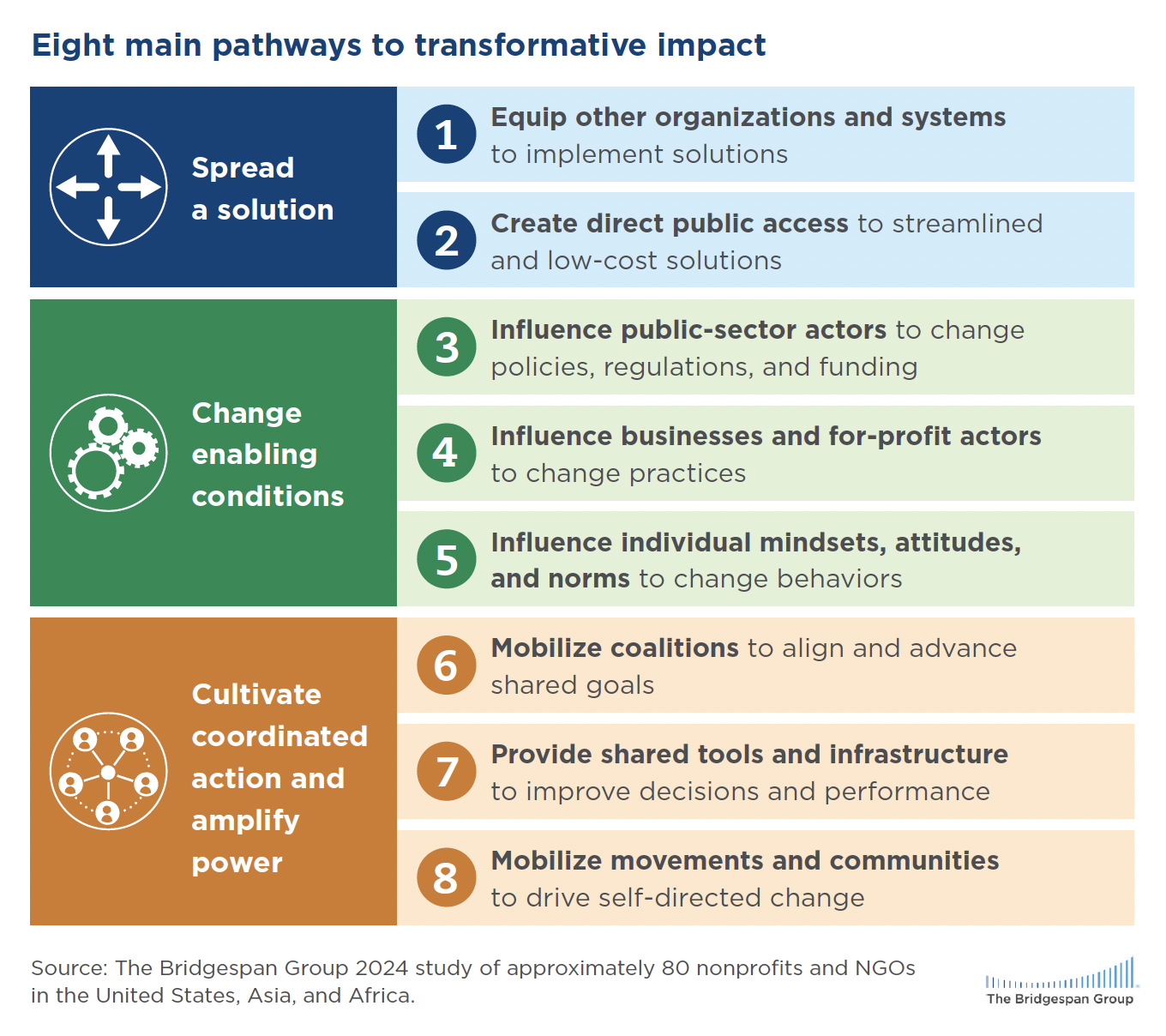

Pathways to Solving Social Problems at Scale

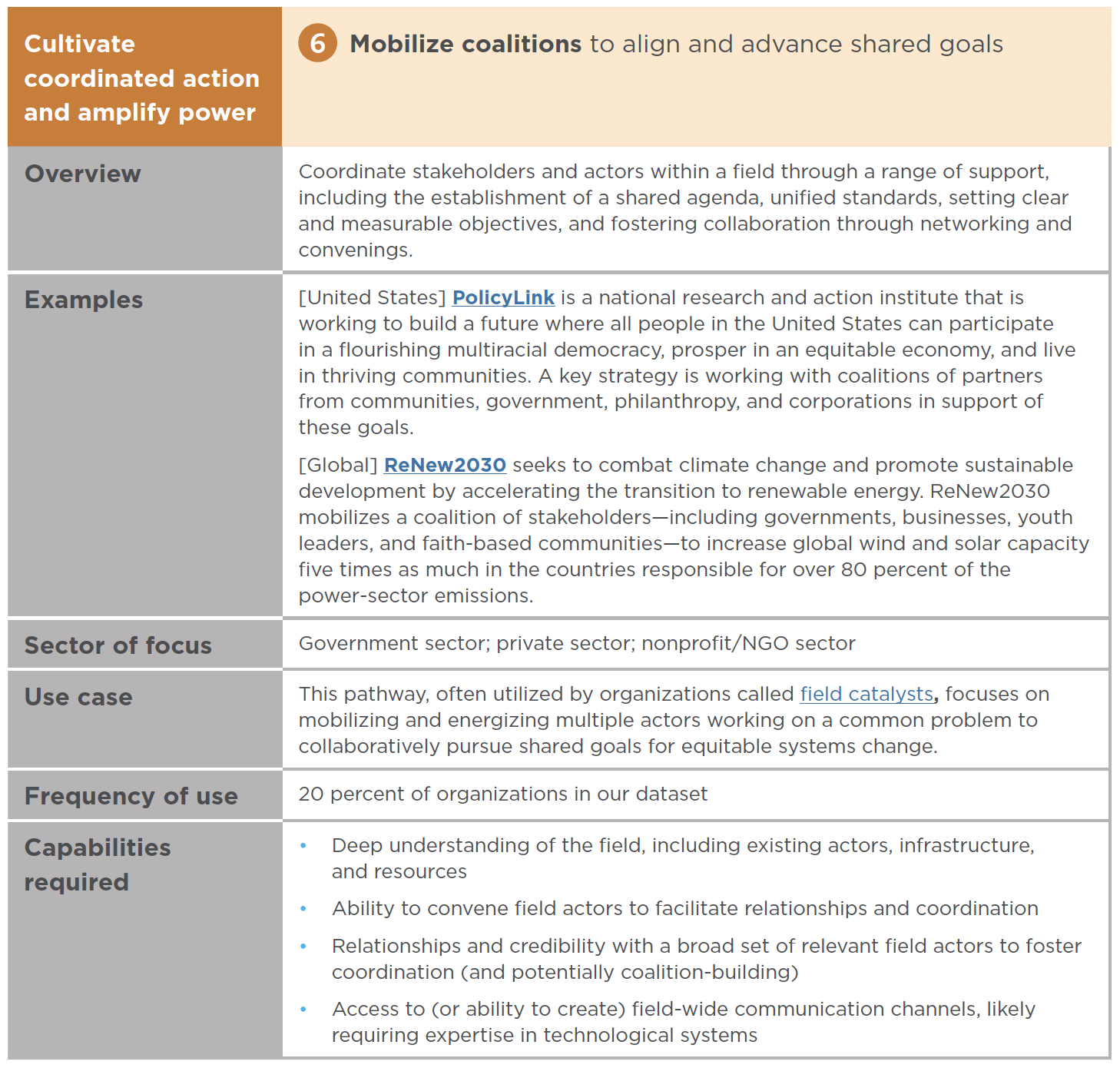

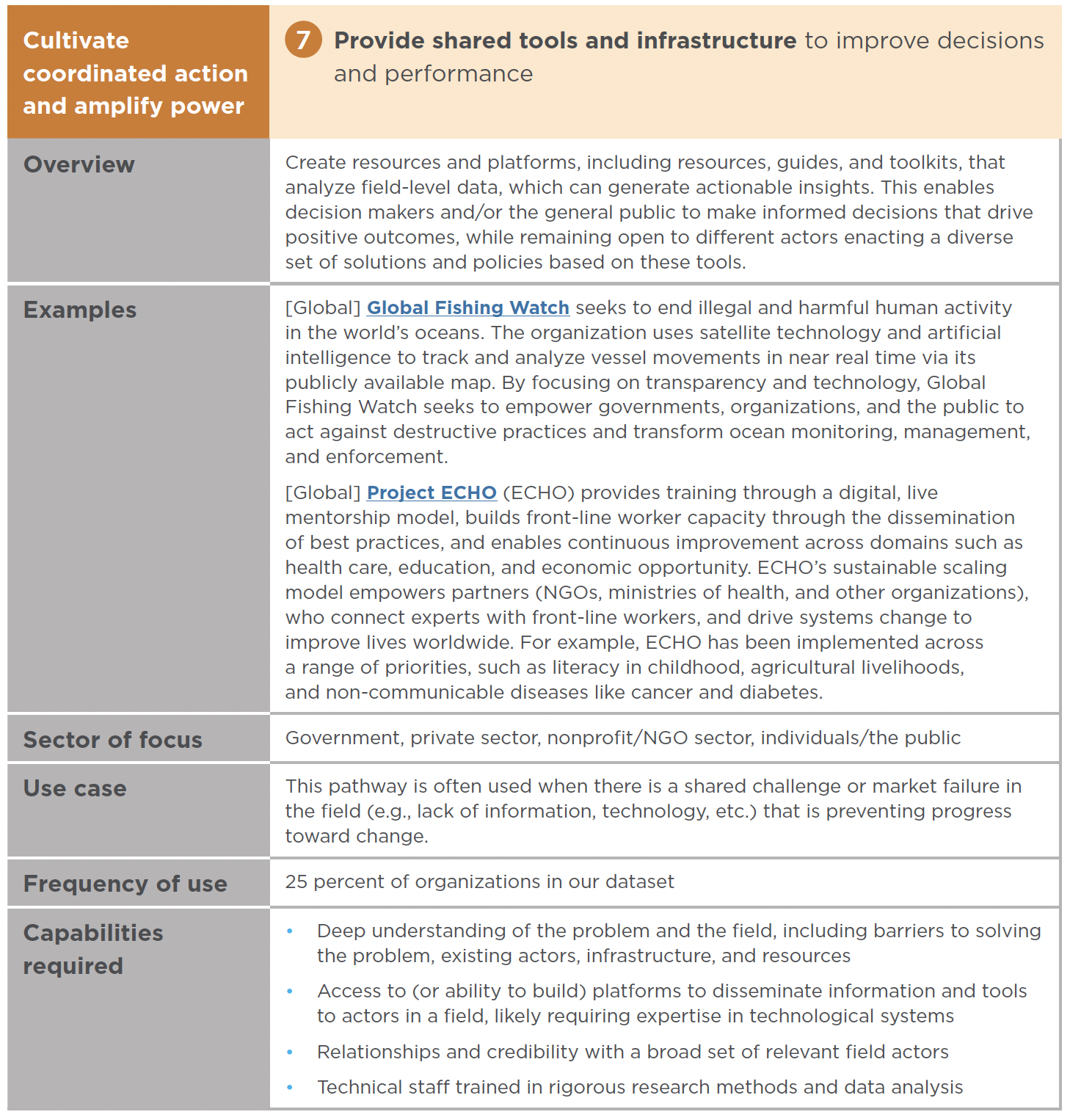

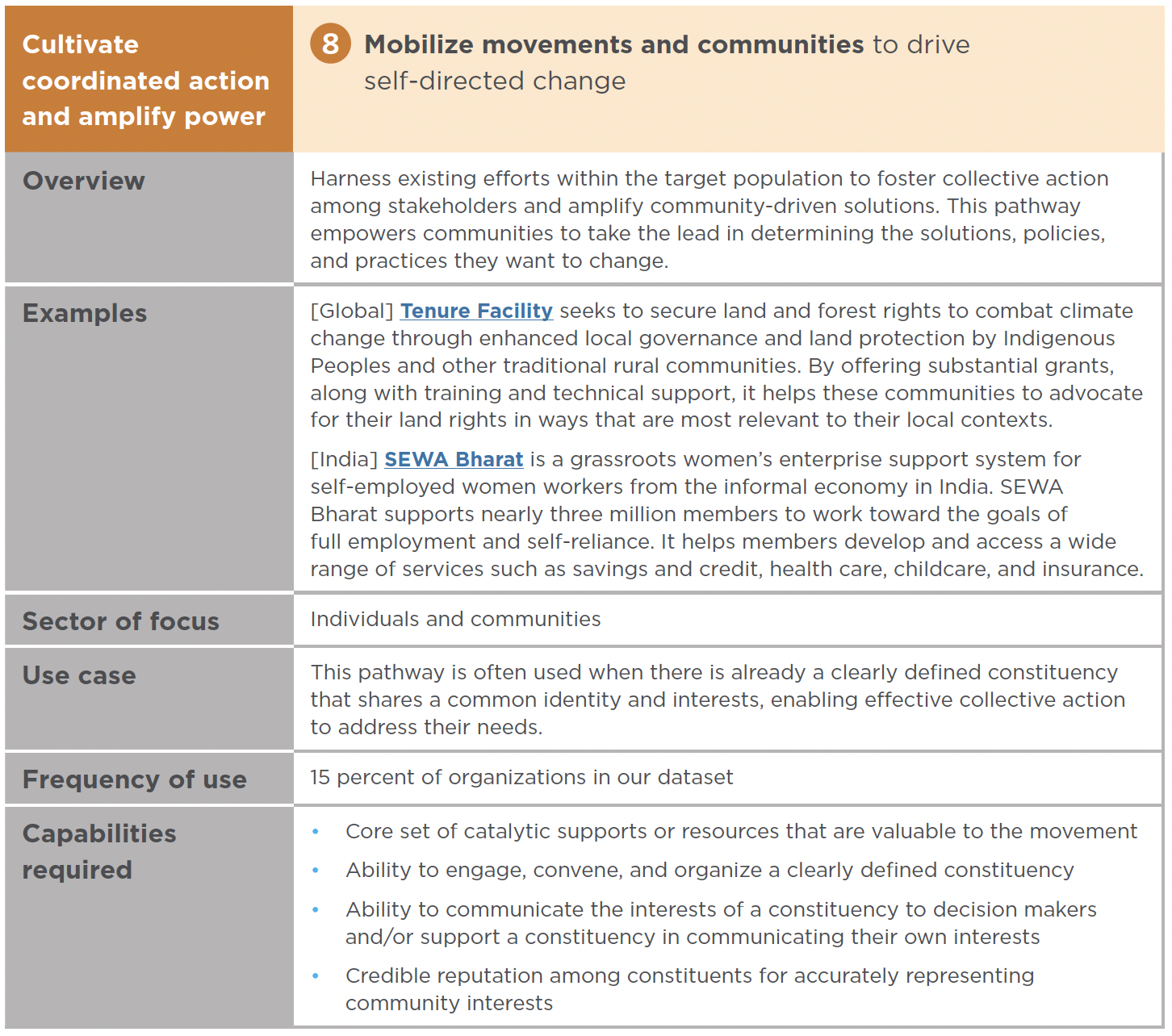

Through our recent research, we have identified eight main pathways, falling into three categories, through which nonprofits and NGOs are working to solve social problems at scale across a wide range of fields, geographies, and strategies. These eight pathways represent an evolution of our perspective from the original article. They build from the insights and pathways identified there, informed by an additional decade of experience collaborating with scaling organizations in a dynamic range of political and social environments across the globe. (We highlight references to the categories and pathways in the remainder of the article as a reminder.)

For more information on each pathway—the contexts in which each is commonly used, examples, and the organisational capabilities commonly associated with each—see “Eight Pathways to Solving Social Problems at Scale” in the Appendix.

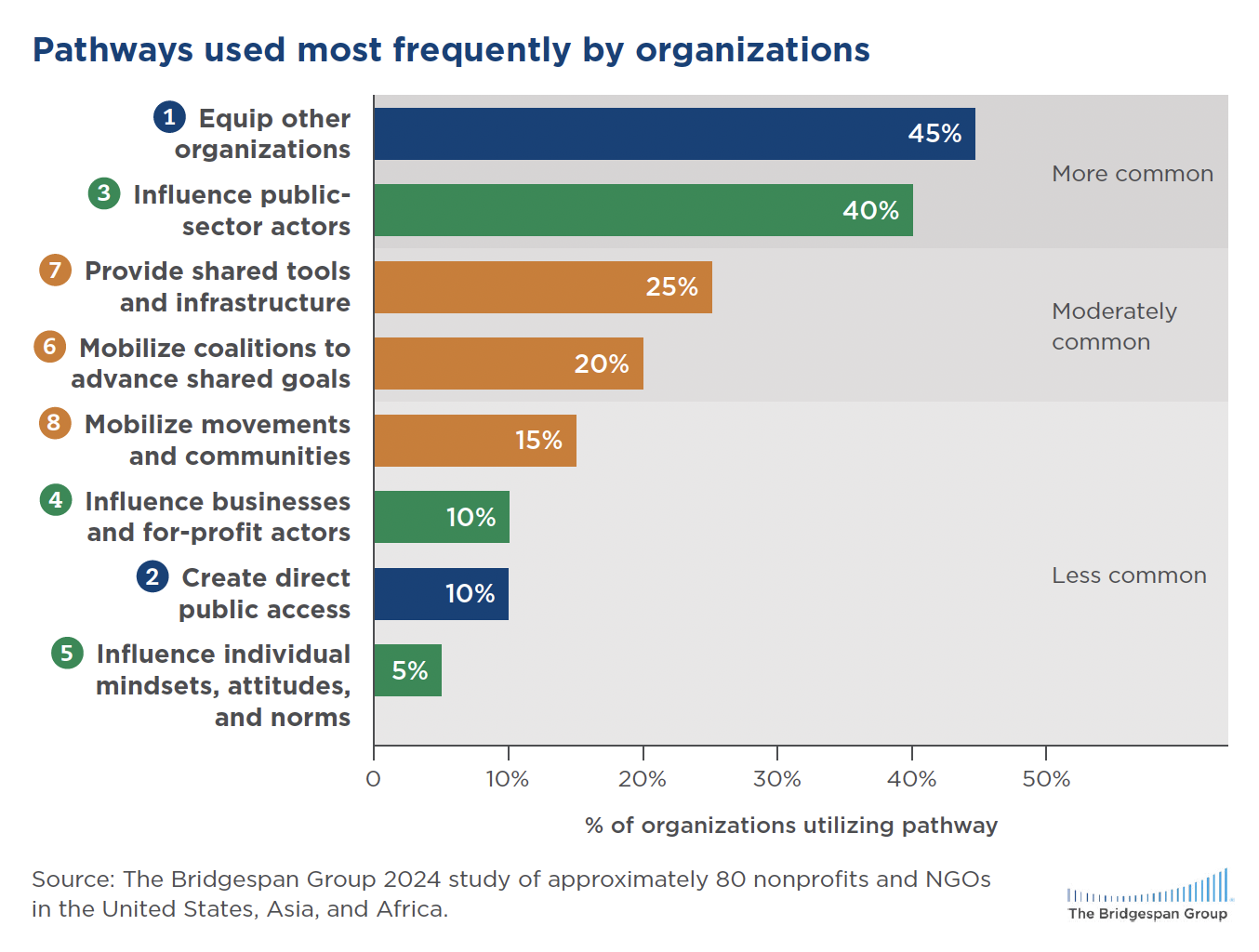

Achieving durable and equitable population-level impact often requires an ecosystem of organizations and actors pursuing all of these pathways, along with providing direct services. However, each organization is likely to focus its work on a subset of the pathways. The choice of pathways reflects an organization’s judgment about the most effective role it can play in helping to solve a social problem at scale. Here is how frequently each pathway is used among the 80 organizations we examined.

Other key findings from our research:

Organizations identify the unique contributions they can make and select their pathways based on their expertise and the role of other actors in the field. Solving social problems at scale requires substantial changes in the entrenched systems that invariably perpetuate inequitable outcomes. Different organizations will play different roles in working toward these changes. Each can make a powerful contribution by focusing on the highest-impact role it can play within the larger group of actors, while partnering with others pursuing different pathways toward the shared goal.

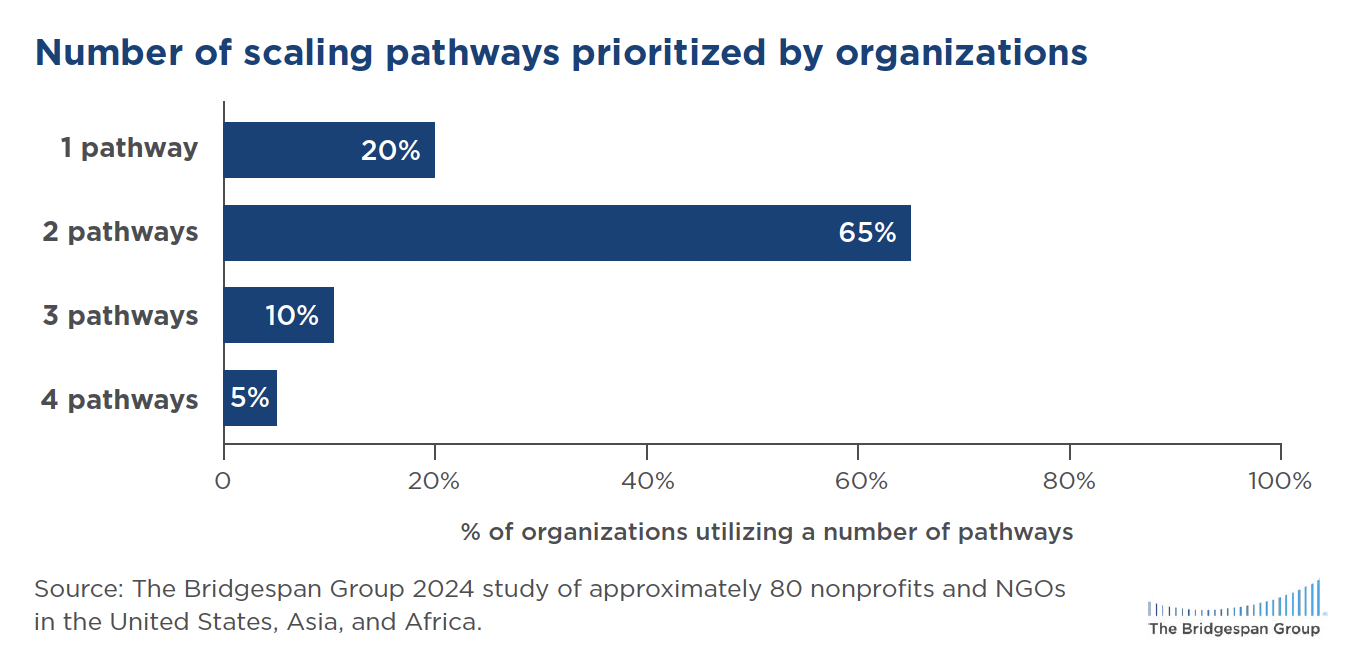

Carving out a specific organizational role does not necessarily mean limiting work to just one pathway. In fact, 80 percent of the organizations in our sample focus on more than one pathway, with most prioritizing two pathways. This makes sense, given the complexity of the problems that these organizations are trying to solve. Organizations can draw from

their experiences, relationships, and credibility to define a subset of pathways that are feasible for them to advance, and which can accelerate progress toward their vision of solving a social problem. At the same time, each pathway often requires a distinct set of capabilities and resources, so organizations are careful not to bite off more than they can chew. Relatively few organizations pursue three pathways as parallel priorities, and even fewer pursue four.

Still, identifying a unique role can mean focusing on a single pathway, as the remaining 20 percent of organizations in our sample have chosen to do. In such cases, the most common pathways selected are create direct public access, such as a digital platform that allows consumers to access educational content or a financial service that was previously inaccessible to them, and provide shared tools and infrastructure, such as a database that gives leaders across sectors new insight into how a complex system is functioning.

For example, Thorn provides scaled products that help drive collaborative response and research to empower professionals working toward responding to and preventing child sexual abuse. These two pathways often involve technology and may require deeply specialized capabilities.

Most organizations pursuing multiple pathways combine them across three categories: spread a solution, change enabling conditions, and cultivate coordinated action. This reflects the importance of complementary efforts in driving durable population-level change.

The most common combination we found was spread a solution and change enabling conditions. For example, Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) pairs low-income, first-time mothers in the United States with nurses who provide home visits from pregnancy through the child’s second birthday, addressing disparities in maternal and infant health and early childhood development. It has grown its impact by equipping local partners to provide this intervention. However, given the large role public funding plays in the US health care system, NFP has also worked with a range of stakeholders to advocate for the public sector to provide more funding—helping to secure a major expansion in federal funding for maternal and child home visiting. In health, education, and other fields where the public sector plays a central role, several organizations in our sample focused both on equipping other organizations and systems to deliver an intervention and on influencing public-sector actors.

Another common pairing brings together the change enabling conditions and cultivate coordinated action categories. Consider the example of ReNew2030, which seeks to drive a global shift toward renewable energy like wind and solar. The global coalition works not only to inform government policies, but also to support grassroots organizing to mobilize communities toward aligned renewable energy goals, and on finance, narrative-building, and legal strategies.

For practical guidance on choosing and pursuing pathways for solving social problems at scale, see “Three Questions for Nonprofits That Want to Solve Social Problems at Scale” on Bridgespan.org.

Organizations pursuing this combination of pathways serve as field builders or field catalysts. (For more about organizations that build and catalyze a field or movement, and how they operate, see additional Bridgespan insights on this kind of work on Bridgespan.org.)

An organization’s choice of pathways is just the starting point for successful impact at scale. Nonprofits must then build the capabilities needed for strategy implementation, and they must adapt their work—and potentially their choice of pathways—as circumstances change.

Marina Fisher is a partner in The Bridgespan Group’s Boston office, where Alyson Zandt is a principal. Angie Estevez Prada is a consultant, Paola Jimenez-Read is a senior associate consultant, and Bradley Seeman is an editorial director. They are all based in Bridgespan’s Boston office.

The authors would like to thank Katherine Herrmann for her work on this research, and Jeffrey Bradach and Abe Grindle, authors of the original 2014 article on transformative scale, for their support and insights in developing this new article.

Appendix: Eight Pathways to Solving Social Problems at Scale

– By Marina Fisher, Alyson Zandt, Angie Estevez Prada, Paola Jimenez-Read, and Bradley Seeman

Harambee in the News

30 Jan 2026

Harambee in the News: January

A snapshot of where Harambee Youth Employment Accelerator was featured in the media this month, reflecting ongoing conversations around youth employment, inclusive hiring, and the partnerships helping to connect young people to meaningful work opportunities across South Africa.

Harambee in the News

18 Feb 2025

Harambee in the News

15 Jan 2025